On November 13th 2018 hundreds of armed policemen arrived in the early morning at Piazzale Maslax, a parking lot in Rome were around 300 hundred migrants, refugees and asylum seekers were camped. The informal camped named from Maslax Maxamed, a 19 year old somali who committed suicide after having spent months in Rome, having travelled to Belgium and having been sent back to Italy because of the Dublin treaty rules. In his first experience in Rome, Maslax had been hosted in a camp similar to the one named after him.

Both these informal camps are the product of the volunteer work carried out by Baobab Experience, an association that was born after people started helping transit migrants and refugees next to the Tiburtina station in the Italian capital. «Our group should not exist, taking care of these men, women and children should be the job of the municipality of Rome and the Italian State» says Andrea Costa, one of the leader of the Baobab group.

The first camp was evicted a few months before November. After that police arrived many other times at Piazzale Maslax. The Baobab experience group had asked many times to the municipality of Rome to find a roof for the people they helped.

The Baobab case is the perfect example of the way immigration is managed in Italy: an eternal emergency.

3 numbers

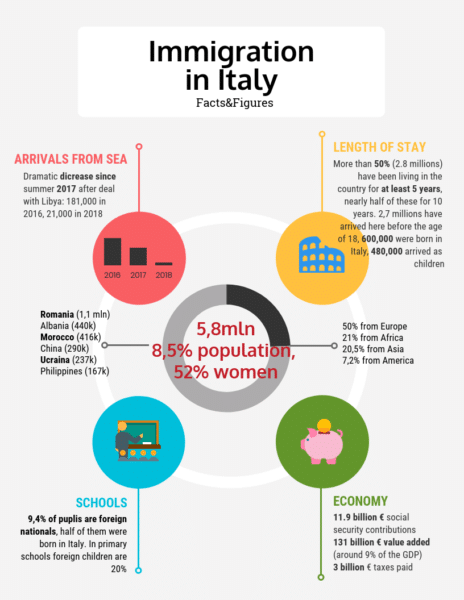

Between 2016 and 2017, the number of migrants living in Italy increased by 97,000. That brings the share of migrants in the overall population to 8.5% (up from 8.2% in 2016). This proportional change, however, is not due to the new arrivals but a decline in the number of Italians, as the birth rate continues to fall and the country ages. For the first time, the total number of deaths exceeded new births in 2017.

Meanwhile UNHCR data show the the number of people arriving on boats from the North African shores has dramatically decreased – declined sharply —from 181k 181,000 in 2016, 119k to 119,000 in 2017, and just 21k on October 21,000 at 31st the end of October 2018 according to UNHCR.

These three figures should be enough to debunk the narrative claiming that claims Italy is facing faces an “invasion” from Africa. It is simply not true, as it is not true that the caravan walking from Honduras to the US Border with Mexico was filled with undercover Isis foreign fighters and gang members.

The Minister of the Interior, Matteo Salvini—who has made the “Italians first” slogan the guiding principle of his actions—has taken many unnecessary steps to put migration at the center of the political agenda to create a sense of urgency and anxiety over the issue.

Against NGOs

The war of words against NGOs ships rescuing people in the Mediterranean has a long history. It started well before the March 2018 electoral campaign and was translated into action after the Conte government formed. There are now many fewer—perhaps no—ships saving people for drowning. Local mayors and civil society groups who have made inclusion of migrants a signature policy have come under attack.

When judges ordered the arrest of Riace’s mayor, Mimmo Lucano, for alleged wrong doing in the management of public funding the government rejoiced: “You see? There is something wrong with this people”. Lucano’s village has been studied and adopted as an example of best practice in migrant integration and solidarity around the world; he is not accused of any wrongdoing for personal profit. A similar case is the recent inspection at the refugee center managed by Don Biancalani, a catholic priest, in Pistoia.

Late one evening in October, 50 police, fire fighters, labor and health inspectors visited the center unannounced, apparently searching for “irregularities” of one sort or another. Don Biancalani called it “an intimidation”.

In August, the Matteo Salvini refused to grant an Italian Coast Guard vessel—the “Umberto Diciotti”— carrying 190 migrants rescued in the Sicilia Channel the right to dock in an Italian port. The rationale for this was that if no other European countries would agree to house some part of them, Italy alone would not take the burden of the maritime arrivals. Salvini was right in denouncing the lack of solidarity among European Union member States. But what followed was a game of chess around the destiny of the 190 people.

Eventually the ship docked in the port of Catania, in Sicily. The next step was to prevent the migrants from landing. After more delays, more controversy—and dueling with Europe, international maritime laws and the mainstream media—the migrants were finally given the green light. The Italian government had nonetheless flexed its muscle to the world (and to its electoral base).

What is the “Salvini decree” on immigration

Moreover, the government has kept the spotlight on the migration issue, through the introduction of new, restrictive regulations. In September, Salvini proposed a Decreto sicurezza e immigrazione (Decree on Security and Immigration)—an urgent administrative rule can operate for 60 days before being converted to permanent law via parliamentary vote.

The new rule—widely known in the English-language press as the “Salvini decree”—signed by President Sergio Mattarella on October 4, brings several changes to the immigration law introduced by the center-right majority in 2002 (Legge Bossi-Fini). The new regulation abolishes the legal category of humanitarian protection, a form of protection for those not eligible for refugee status but who for various reasons cannot be sent home.

A significant portion of those arriving by sea receive this kind of protection but are disparagingly called “phony refugees”. Many of them come from regions of Nigeria or Pakistan (to give two examples) where they are not necessarily persecuted by state authorities but by local political or religious groups.

This protection will be replaced with permits that will limit eligibility to people such as victims of a natural disaster or those with a serious illness. The law also brings changes to the citizenship status of foreign-born people. Those who commit certain crimes will be stripped of their Italian documents. Stripping a person of her nationality is a dangerous legal precedent. The new rules also double the time bureaucracy can keep a person waiting the result of the naturalization process to 48 months.

New rules are set also for those who manage to get in the country but are not immediately offered legal protection face much longer processing times and the risk being expelled. While the period of detention has been modified on many occasions by different Italian governments over time, the ratio of people repatriated has remained more or less steady. Keeping people in detention for longer is not a solution to the difficult legal problem of sending them back to third countries or to countries that do not want them.

The last change introduced by the regulation is to the system of receiving and hosting new arrivals. Italy, with its long coastline and proximity to Africa—which means it is a constant source of maritime arrivals—is way behind other European countries.

In 2017, 80% of the 187,000 asylum seekers waiting for a determination of their legal status and a permit to stay were hosted in Extraordinary Reception Centers or CAS, while 13.15% remained in the so-called Protection System for Asylum Seekers and Refugees (SPRAR).

The latter is a decentralized system that offers more tools for integration and inclusion of refugees and has a lesser impact on local authorities—with migrants spread in relatively manageable numbers in every village, city, and town. SPRAR is the optimal way of managing people living in legal limbo. The number of people hosted by the SPRAR system has been growing in 2018 (+4,000 accomodations available), while the number of people perproject remained low (8 per community), guaranteeing a low impact of the asylum seekers presence.

The “Salvini decree”, however, favors the opposite—constructing more CAS and having more people detained in large centers. This will translate in more violations of human rights, less inclusion and more precarious situations. And more visibility for migrants and asylum seekers that cannot work and are not offered language or training courses.

Many majors involved in the Sprar system, both from the centre left and the centre right, have complained about the new rules, as did the non partisan national association of municipalities (Anci). A bad policy solution, a perfect political trick.

Who are the immigrants in Italy

How bad are these policies for an aging country like Italy? And are the target of these policies—asylum seekers coming by sea—a major part of Italian immigrants? The simple answer is no. More than 50% of immigrants in Italy (2.8 million) have been living in the country for at least 5 years; nearly half of these for ten years or more. Of the over 5 million immigrants in the country, 2.7 million have arrived before the age of 18, 600,000 were born in Italy and 480,000 arrived as children (i.e. under the age of 12).

Only 16% of immigrants living in Italy have been living in the country for fewer than 5 years. Italian is used in 1.3 million foreign households and 90% of those under 18 speak Italian with their friends. Some 90% of foreign workers speak Italian in the workplace—with the exception of Chinese speakers, often employed by Chinese entrepreneurs as elsewhere in the world.

In Italian schools, slightly fewer than one in ten is a foreigner. In high schools, the figure is 7%, in pre-primary and primary (ages 4–6 and 6–10, respectively) it is 11%. Two thirds of these kids were born in Italy but have no citizenship (the corresponding figure was 30% in 2008). The high number of children in the first grades of school throws a light on a huge demographic issue: the number of newborns is smaller than the death rate, with the only source of population growth being immigration.

What about the economy? Immigrants make €11.9 billion in social security contributions, add €131 billion in value (around 9% of GDP), with €3 billion in taxes paid. These are the data. Then there is the contribution to society as a whole—in schools, neighborhoods, workplaces and in enhancing the exchanges with the rest of the world. Migrations also bring questions, how else could it be? But focusing on continuous “emergencies” diverts attention and resources to face them with effective policies.

What happens where the far-right wins

In many cities and regions where the far-right is in power, municipalities have issued regulations to discriminate against foreign-born people and make it more difficult to access public welfare services. In Lodi, a small city near Milan, foreign-born kids in school had to provide a series of documents to prove their families were not wealthy in their country-of-origin in order to pay the normal rate for the school lunch (otherwise the cost is triple).

These kinds of documents do not exist in the same format in many countries. In other cases, the cost of obtaining them would be greater than the value of the meal subsidy in school or could take months or years to secure. Italian civil society was so outraged by this move, that sufficient funds were raised in donations in just one day to cover the cost of the kids’ lunches for a year.

The Regione Liguria and Veneto have also issued regulations that give priority access to services (housing, healthcare, childcare) to people who have been living in the Region for at least 15 years. This is just pure discrimination against foreigners and people coming from other regions. Indeed, let’s not forget that Lega—before being a far-right party, was a regional xenophobic party that would openly look askance at Italians from other parts of the country.

These municipal regulations—and many more besides—were disallowed by Italy’s Constitutional Court, but local authorities continue to assert them even knowing they have been struck down. These local regulations therefore are not effective policies—they are just tools of political mobilization.

Right-wing and center-left governments have ignored the numbers, the problems and the opportunities related to immigration. During the last 10 years or so there have been almost no legal ways of immigrating to Italy. The tool that regulates immigration to Italy—the “Decreto flussi”—includes an annual quota of work permits that can be issued to foreigners by consulates at their discretion.

For many years—with exceptions regarding seasonal workers and others—the number issued has been close to zero. Not enough resources have been allocated to integration and training of migrants, with all the attention going to the “maritime emergency”. This has been a boon for Salvini’s Lega and bad for the left in term of consensus: if you root for the bad cop, you vote the original one.

Photo: ANDREAS SOLARO / AFP

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).