At a time when colonial history and its legacy is becoming an object of controversial debate worldwide, ethnography museums can play a key educational role.

The recent Black Lives Matter protests against statues representing public figures related to or associated with the slave trade, colonialism, and racism have reopened a debate about the role of historic symbols in the public space. This debate, which has been key in the fields of anthropology and museology over the last fifty years, has now gained visibility outside the academic realm. All over the world, ethnographical museums have been facing the following question: what to do with ethnographic collections, which explicitly or implicitly are related to colonial history and an unfair relationship between former colonial states and colonies? How to display architectures that bear witness to racism like the famous building of the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium or the building of the former French Museum of Colonies now transformed into the National Museum of History of Immigration? French anthropologist Jean Jamin had ironically suggested burning all these collections. But burning these objects is unlikely to solve the problem, as it would cancel the history of these objects, of the people who produced them and of those who brought them to the museum (fairly or unfairly).

Undeniably, many items that are on display in museums in Europe, United States, Canada, Russia, Australia and New Zealand were taken, looted, or bought at a time of unfair and asymmetric power relations. Even Switzerland, which had no formal colonies, owns important collections that are related to colonial history, as well explained by Boris Wastiau, director of the Geneva Ethnography Museum (MEG), in an upcoming interview to this journal. Some objects and buildings bear witness to a time in which science and anthropology were linked to the idea of a hierarchy of cultures. This perspective was defined by the idea that colonialism was a tool to bring civilization to colonies. Ethnography museums had the purpose of constructing an image of an exotic and primitive world to be distinguished from the civilized world, through the exhibition of a variety of non-European objects. Many scholars have defined this approach as “cannibalism” as the approach consumed other cultures’ objects while silencing those who fabricated them[1].

The long path of self-reform

After strong criticism and post-colonial influences over the last decade, a “symbolic revolution” shook the field of ethnographic museums in Europe. Most museums implemented innovative strategies for a more reflexive museology [2] and followed a new deontology in order to reshape their colonial heritage. Many were completely renovated; others changed their name and museographical approach. Instead of ethnography, which is too close to the colonial context, most museums today prefer the denomination “world cultures”, “civilisations” or “world”, in order to build a new framework of reference, related to the post-colonial and globalised order. From Paris to Vienna, from Bale to Tervuren, many institutions have changed their name, their narratives and their displays in an attempt to critically discuss their colonial origins. Although this process has not always been clearly understood by visitors, undeniably the post-colonial critique has reduced the distance between the museums as centres of power and world’s peripheries, from which most collections and represented peoples come from. Those peoples, who used to be represented as objects of study, now claim to represent themselves within the museum display, to interpret their history and to manage or return their collections.

In parallel, a new international moral and legal context has flourished since the 1980s with the evolution of UNESCO and ICOM norms, the rise of indigenous’ rights awareness and the introduction of the intangible heritage category. The normative approach, therefore, of cultural diversity, the adoption of intercultural dialogue, and the various attempts to recognise previously invisible groups (be they former colonized peoples, indigenous peoples, or migrants) became the museums’ new discourse.

Unanswered questions

Besides this symbolic revolution, many ethical and political questions remain unsolved. What is the essence of heritage? Is it a universal public good or a particular tool for preserving and fostering the memory and identity of a specific group? How to set a base-line for the equal treatment of objects, which are on display in different museums all around the world? Why are the majority of objects on display in museums in Europe and in the United States if they come from African or Asian regions?

In a famous speech delivered in November 2017 in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, French president Emmanuel Macron announced that it was time to return cultural objects to African museums. This undoubtedly opened a Pandora’s box. At his request, a scientific and detailed report on the nature of French heritage was completed in November 2018 (the Sarr-Savoy report). It called for the restitution of many objects from Western museums to their countries of origins. Nevertheless, this restitution process raises many problems. On the one hand, at a national level, French laws are very strict about national museum objects, considered as “inalienable”. In order to return a single museum object, a specific piece of legislation needs to be created and voted by the French Parliament. On the other hand, the return of cultural objects is a very international issue. It is extremely complicated to compare different heritage legislations with regard to the same group of items, located in different museums across Europe and the US. Except for cases of documented theft or looting, it is hard to identify the specific provenance of objects and to establish where and to whom they should be returned.

Behind all these legal questions, restitution remains very much a political issue. The increasing international legislation on the return of cultural objects should be interpreted along with the “internationalisation of multiculturalism”, to use Will Kymlicka’s definition. The historian Elazar Barkan called it a Post-Cold War international justice based on morality and restitution. In his opinion, the rising number of claims for restitution worldwide is the sign of a new policy in international relations. Accordingly, restitution should be considered as a tool for repairing historical wrongs, reconciling memories and giving visibility to indigenous peoples and former colonised countries. To this extent, restitution is a way of implementing an international politics of recognition in a guilt/victim relationship and museums are the battlefields where this process is taking place.

Beyond restitution

What should be done with colonial collections? Should museums return all items to their countries of origin even when it is not clear to whom they belong? The Anglo-Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah exposed all the facets of this dilemma. Following a cosmopolitanist approach and criticizing an essentialist or nationalist perspective on heritage, Appiah explains that there is no direct link between the Nok civilisation and the contemporary state of Nigeria, nor between the Viking people and the people living in contemporary Norway. Heritage should not be considered as the possession of a single culture, because people and culture change over time, exchange with each other and are not fixed entities.

Undoubtedly, in the case of proven theft or looting, restitution should be encouraged and accomplished. But it should not be a magical solution to all heritage-related issues. The debate between universalism versus restitution follows a counterproductive path. There is no clear line in favour of one or the other. Knowledge depends on its transmission and its public; likewise, heritage should be available to the largest possible audience, especially in developing countries. Science makes progress only when its results are shared internationally. Likewise, collections need to be shared with visitors all over the world. A “transnational shared heritage” with long-term loan-policies, mobility of collections and museum professionals, partnerships between institutions in terms of research, exhibition and cooperation, sharing of heritage interpretation and sharing of different memories would be much more influential than simple restitution.

Therefore the main question that needs to be addressed concerns the role of museums in our society today and for the next decade. Restitution is just one part of the picture, but the main mission of a museum is above all educational. Museums can be a very powerful instructive tool touching history, society, politics and economy. They should be considered educational institutions like schools, with a particular mission: they bear witness to a divisive and sensitive past. This might prove to become their strength if they succeed in displaying this past with diverse narratives. Cancelling or hiding their collections would be a mistake because it would contradict their very mission. On the contrary, displaying critically and explicitly their history with its prejudices, conflicts and racist ideologies and showing the different narratives in the interpretation of history would bring a lot of value to current and future generations. The permanent installation Whose Objects? at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm is an outstanding case of multi-vocal display. It shows 74 pieces of the famous Benin collection that was looted by British troops in 1897 and sold afterwards to many museums in Europe and the United States.[3] The exhibition compares different viewpoints on the topic of restitution, clearly underlying the history of these objects and the history of their circulation.

To this extent museums can play a fundamental role in our fragmented and disoriented societies: they can teach world history – and in particular colonialism and the link between science and racism. Burning statues or symbols of this divisive past is not the solution to a very complex problem. History has been always made of wars, conflicts, slavery and power relations. By adopting Thucydides’ realist approach to history, we should leave emotions and moral judgments behind while analysing the past. To make our future more cohesive and inclusive we need to build a shared and multi-vocal memory. All ethnography museum collections, thanks to their contentious origin, have the power to do so.

[1] Gonseth M-O., Hainard, J., & Kaehr, R. (Eds.), (2002). Le musée cannibale. Neuchâtel: Musée d’ethnographie.

[2] Pagani, C. “Exposing the Predator, Recognising the Prey: New institutional strategies for a reflexive museology”, ICOFOM Study Series [Online], 45 | 2017. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/iss/341 ; DOI: 10.4000/iss.341

[3] Whose Objects? Art Treasures from the Kingdom of Benin in the Collection of the Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm edited by Wilhelm Ostberg Stockholm: Etnografiska Museet, 2010. Bodenstein, F. & Pagani, C. “Decolonizing National Museums of Ethnography in Europe: Exposing and Reshaping Colonial Heritage (2000-2012)”, in The Postcolonial Museum. The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History. 2014. Ed. by Ian Chambers, Alessandra De Angelis, Celeste Ianniciello, Mariangela Orabona. London: Routledge, 2014, pp. 39-49.

Camilla Pagani, PhD, is Lecturer in Political Theory at MGIMO University, Moscow, and Sciences Po Alumni Board Member.

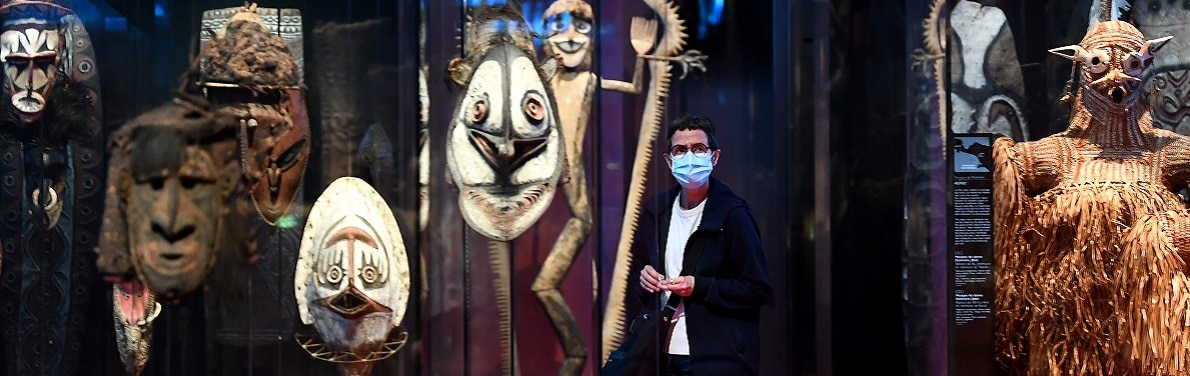

Cover Photo: Franck Fife/ AFP

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to share and interact with our contents.

If you like our stories, videos and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).