An unpredictable turn of events in Russia on Friday June 23, when in the final hours of the day news of what appeared to be a coup emerged. Sergei Prigozhin, or “the politician of questionable perspectives” (Politik s Somnitel’nymi Perspektivami), as his Wagner soldiers now call him, rode into Rostov from an unknown hideout, launching what he called a “march for justice” (Marsh Spravedlivosti) aimed at punishing those in the Kremlin responsible for the disastrous war in Ukraine for their ineptitude and corruption – Prigozhin never explicitly mentioned Putin, but laid the blame on Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu.

This unexpected move was over just as rapidly as it had begun, when about twenty hours later Prigozhin meekly called for a general retreat, claiming that he had achieved his goals just as his forces reached the outskirts of Moscow. For international onlookers, ordinary Russian citizens, as well as for analysts and historians, this was a baffling turn of events. To better make sense of what happened as well as of the Russian government’s reaction, let us draw a couple of historical parallels.

Rebellious precedent

Starting from the peripheries closest to the frontlines in Ukraine, Prigozhin’s rebellion may remind that of the legendary Cossack Sten’ka Razin against the Russian empire in 1670. Starting from the far-off Siberian provinces, the Cossack led a movement against the nobles and boyars, acclaimed by the local peasantry. Razin paid a steep price for his treason: after his movement failed to gain momentum, the ataman was delivered to the Tsarist authorities and then quartered and hanged throughout Moscow as a memento while the Imperial Army unleashed a bloody wave of repression on his followers and the general populace. Only it seems this time, Prigozhin simply decided to turn back and leave his rebellion to fade away.

A much similar event took place during the early Stalin years in August 1934, when the Politburo was surprised by the news of a mutiny among the “Osoaviakhima” artillery brigades. Young Brigade Commander Aleksandr Nekhaev, assembled his men and delivered a grand speech against the Communist Party and Stalin, who according to him had brought the country into misery and broken the promises of liberation of the revolution. The rebel was quickly captured the day after being handed over by his own men, and after long interrogations, shot for treason. However, after the ordeal was over, Stalin commented how the rebel had probably been an agent of Poland, or Germany or even Japan, a grim anticipation of the absurd accuses that were to come in the Great Purges a few years later.

Razin’s and Nekhaev’s rebellions point out two usual Russian reactions to rebellion. The first is a sad tendency towards a brutal and bloody repression despite initial signs to the contrary. The second is the tendency of laying the blame on foreign agents for internal strife. Naturally, as of today, it is still impossible for most observers to give a clear-cut analysis of the recent events in Russia.

In Putin’s speech, repression as omission

Let us begin with repression by looking at the Kremlin’s reaction to the events. At around 9pm (Moscow time) on June 23, a galvanized Prigozhin announced a deal had been struck between him and the government forces thanks to Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko‘s timely mediation on behalf of the Kremlin. Soon after, Russian Telegram channels following the event closely were alight with discussions and clashes. Those with links to the Armed Forces mostly cheered Putin for avoiding an ominous turn of events, but lamented a weak reaction to this grave act of treason.

Other channels, especially those close (or claiming to be) to Wagner cried out in anger against their leader and his sudden coup de poignard. Channel members denounced Prigozhin as a “clown” and expressed bitter anger, afraid they will soon be the victims of a “Stalinist-style purge”, drawing many parallels with the brutal repressions of the Commissariat of Internal Services (NKVD) between 1936-38. Muscovites jokingly cheered for the festive day proclaimed by the authorities for Monday June 26 at the height of the crisis.

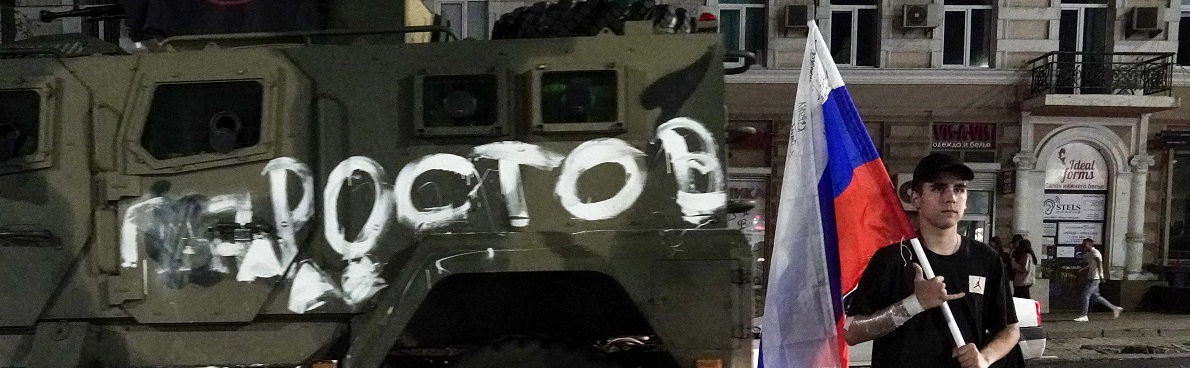

Contrasting videos emerged all over Russian socials and on Twitter of the crowd in Rostov-na-Donu either carrying on with business as usual or cheering and taking pictures with the retreating Wagner mutineers. But while both the streets and social media were brimming with either bickering and\or celebration, a deafening silence defined the Kremlin’s reaction in the first few hours after the deal.

The Kremlin woke up from its slumber (or embarrassment) only between yesterday and the day before. In what the New York Times defined as an “angry speech”, Vladimir Putin thanked the nation and armed forces for their pivotal role in supporting the government and assured that the “rebels had no chance of winning either way”. An important point was implicitly made in this speech.

Vladimir Putin said Russia is facing 'a colossal external threat' days after an attempted rebellion led by Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin.

Watch his full speech below. pic.twitter.com/aOunI5k4id

— Sky News (@SkyNews) June 26, 2023

Putin, who loves history, has worked intensely to portray Russia as strong only when united under a strong leadership. Following this syncretic reasoning, Stalin was a positive figure, despite his excesses, as his strong leadership had led Russia to victory in the Second World War. Lenin and the Bolshevik revolution on the other hand were a catastrophe for the nation, wreaking havoc on the populace and strength of Russia – no matter that Stalin had been one of the most active Bolsheviks as well. That is why Putin drew parallelisms with the 1917 revolution on the eve of Prigozhin’s “March for justice”, a parallelism that finally comes full circle in his “follow-up” speech: rebellion cannot be allowed in such difficult conditions and we shall repeat the errors of the past again. This point is a reminder to both the people and those close to leadership that civil strife would mean suffering for the populace, and an end to their rule for those in power.

Repression, while being the first point of this article, strikingly appears also as a great omission. In his speech, Putin recognized how the leaders of the rebellion were wrong in their assumptions, and realized this just in time to turn back and be allowed to settle in (dangerously) nearby Belarus. Positions in the Army were offered to both those who refused to take part in the rebellion and those who did.

Putin probably wanted to portray a fierce image of the victor, reassuring those involved and giving a “pat on the shoulder” to the obedient state officials. Yet the rebellion remains a fact, and a serious one at that. A fact no doubt that the Kremlin will have to answer for before its citizens, if nothing else with a production of a narrative of events, which the Kremlin may be short of at the moment.

Internal reactions between criticism and loyalism

A look at the reaction inside social media (given above), state TV and newspapers across the factions might help understand what kind of narrative is shaping around the events. Vladimir Solovev, the Russian anchorman known for his strong support of the war and the establishment in general, dedicated a full two days of his tv program (on June 26 and 27), Evening with Solovev, to the events. Solovev began his daily broadcast with the words, “Yesterday was scary”, but quickly followed along the lines given by the Kremlin, stating how the rebellion was only supported by Russia’s enemies, furthering the rebellion-foreign intervention dichotomy presented by Putin. He added, addressing the Wagnerites: “Thank you for yesterday, but today we need answers!” referring to the company’s role in Ukraine, and mentioning how many of the soldiers inside Wagner realize that “they should be at the front with their brothers”.

Parallels between the 1917 October revolution dominated the rest of the transmission and next day’s episode, working to further underline the link between treason and foreign intervention as well as calling back to the tragedy of the “fratricidal” 1917 events. Harsh punishment, or “annihilation” as one guest put it, was called for the rebels. TV news outlets simply limited themselves to giving a glowing retelling of events, merely reporting about the uprising and the Kremlin’s statements.

Interesting comments on recent events also came from two important Russian ideologues, Aleksandr Dugin and Vladislav Surkov. Dugin commented the events in his Telegram channel, on his personal blog and even on Russian TV, on Dimitri Saims’s Great Game show. In an article on his blog geopolitica.ru, (then reiterated on TV) Dugin commented sternly on the rebellion, criticizing severely the government’s slow reaction to the events, using the concept of passionarnost’. First coined by soviet archeologist and philosopher Lev Gumilev, passionarnost’ is intended as a fierce spirit (literally a ‘passion’) present in Eurasian peoples, as the main galvanizer for their greatest “accomplishments” when at its height, such as during Gengis Khan’s and Peter the Great’s times. In his article Dugin, a disciple of Gumilev, points out how Russia’s passionarnost’ has shifted away from the hands of the State into the provinces, creating dangerous unbalances.

Dugin thinks of June 24 as a point of bifurcation for Russia, proposing two possible outcomes and courses, a good one and a bad one. According to Dugin, the correct step would be “less PR, more reality”. It is necessary to stress Putin’s role in quashing the uprising (thus affirming his power) and, Dugin argues, “rotate the elites, encourage the courageous, rectify state ideology and punish cowards and traitors”. There is then a “shameful scenario” where things would continue the way they are, a case where “the ones with more passionarnost’ will win, and catastrophe will be fatal this time”.

State hawk Vladislav Surkov was less ideological in his remarks, and on a TV interview linked the recent events to Russia’s tragic Time of Troubles (Smutnoe Vremia) in 1620, when Polish intervention in the succession and civil war threatened to destroy Russia for good. Surkov, a former leading ideologue of Putin, compared Prigozhin to a common street thug taking advantage of helpless people, and stressing the necessity for the State to form a coherent and tight power struggle against mercenaries, “a thing of the past”. Both commentors seemed however aware of the lethal danger Russia is facing at the moment.

For the opposition papers inside and outside Russia, such as Meduza and Novaia Gazeta, the uprising generally points to a severe weakness in the current Russian establishment. The two newspapers approached the matter by shedding light on Sergei Prigozhin’s empire and fortunes, while also counteracting fake information circulating inside Russia. Particularly, many concentrated on Prigozhin’s “pioneer” work with Telegram trolls and abuses against those not in favor of the war, and around Wagner’s ties with the Internal Ministry of the Russian Federation. Meduza, refraining from direct interpretations of the events, also asked its Russian readers to publish their initial and post facto reactions to the events on social media and private conversations with their friends and relatives.

The Moscow Times alongside several other Pro-Russian and Ukrainian Sources are claiming that Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Aerospace Forces, General Sergey Surovikin was Arrested by the FSB on June 25th under Suspicions that he Supported and in some way Assisted in the… pic.twitter.com/dFr4Ui8Sv2

— OSINTdefender (@sentdefender) June 28, 2023

The West accused of foreign intervention

After Putin’s speech, Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko, emboldened by his pivotal role, gave a less optimistic vision of events, shedding more light on the Russian government’s weak reaction. After giving some assurances that the exiled Wagnerites would be housed under a cordon sanitaire of sorts, Lukashenko mentioned how the Russian forces could have indeed killed Prigozhin and his rebels, but only at a bloody price seen that “they are nonetheless the most battle-hardened units” of the armed forces. This appears to be in stark contrast to Putin’s optimistic (if somewhat laconic) speech. One thing is clear: Lukashenko secured a strong position and portrayed himself as the man who saved the day. But is this really all there is to it? Seems hard to believe.

While the Russian Internal Security Bureau (FSB) has dropped charges of treason against Sergey Prigozhin and the Wagner Company, and we know Prigozhin safely landed in Belarus, it seems difficult for any observer to believe that exile will be the only consequence for the “traitors” (predateli), as Putin called them.

A sense that a wave of repression is coming is suggested by the words of ultra-nationalist National Guard (Rosgvardia) leader and Kremlin strongman (silovik) Aleksandr Zolotov, who at a public security meeting said that his forces will receive heavy weaponry and tanks, thus greatly enhancing their capabilities. This is a serious turn of events for the Rosgvardia, a military force fanatically loyal to the President and largely controlled by the Kremlin. This development could also suggest that tighter and tighter measures for public security might in all likelihood be employed in the near future to keep a tighter leash on all forms of dissent inside Russia. One wonders if revenge will be forthcoming, how repressive these measures will be and above all, how many will be punished. It needs to be seen whether Prigozhin had some contacts inside the inner circles of the Kremlin and whether we will observe a major reshuffle within the higher ranks. According to several media, Russian General Sergei Surovikin i.e., has already been arrested.

Zolotov and Lukashenko also both accused the “West” of having meddled in Russia’s internal affairs and having incited or financed Prigozhin’s militia. While the rebels boasted their patriotism as legitimation for their actions, Putin also implicitly drew the same conclusions, by linking both “internal and external enemies” as a joint force seeking to disaggregate Russian state unity. The Kremlin might be trying to play the foreign intervention card to explain the potential deadliness of the rebellion (and thus their apparently weak reaction), as well as a means of deflecting public attention into the greater narration of Russia’s enmity against the “West”. This is not new in Russian history, as the exploit was also a means to explain times of serious turmoil (the Purges, for example) as well as to anticipate a steep rise in repression.

Yet such accusations are a far cry from reality. So much so, that even before Prigozhin’s uprising, US authorities expressed considerable concern over his intentions and even warned Russian leadership of the possibility of troubles, fearing that a civil war could break out inside a nuclear capable country, even if a bitter rival. Most European countries followed suit, closely monitoring what clearly appeared to be a serious crisis. Ukraine, for its part, simply hoped to capitalize on the crisis, anticipating it to be longer than it actually was. While the “March” is physically over, the aftershocks of the events will not fade so easily.

Cover photo: A man holds the Russian national flag in front of a Wagner group military vehicle with the sign read as “Rostov” in Rostov-on-Don late on June 24, 2023. Other local people asked the soldiers for pictures and shook their hands (photo by Stringer/AFP.)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.