“I’m ready to meet anyone, including Zelensky.” Vladimir Putin’s recent statement suggested a openness to renewed negotiations – though only “in the final phase.” But skepticism remains high in Kyiv and across Western capitals. The Kremlin’s latest proposal – disarmament, new elections, and ceding of occupied territories – was flatly rejected by Ukraine. Meanwhile, Russia continues to escalate military pressure: just last Tuesday, it launched over 440 drones and 32 missiles in one of the most intense attacks since the war began.

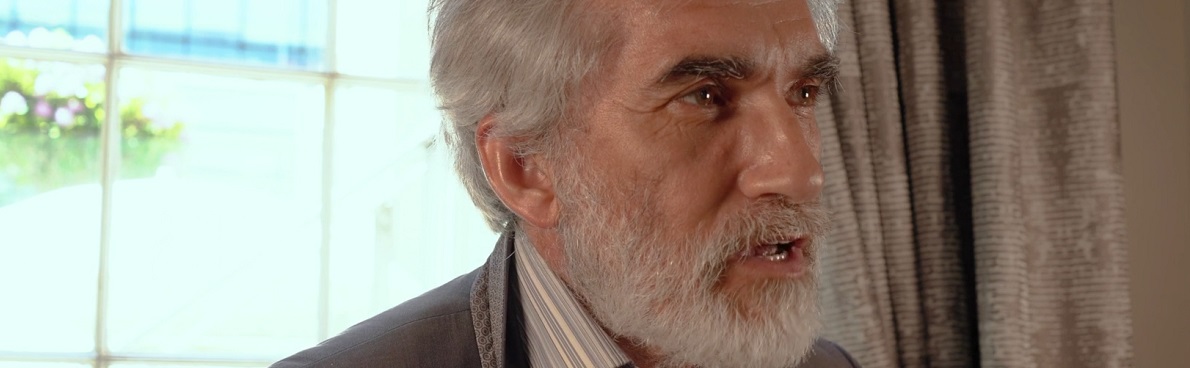

Against this backdrop, Reset DOC interviewed historian Yaroslav Hrytsak on the sidelines of the event The Jewish Question in Ukraine: Between Propaganda and Historical Reality, organized by Boristene and held at the Shoah Memorial in Milan on June 18, 2025. The conversation explored Ukraine’s military position, diplomatic deadlock, Western support, and prospects for peace.

Negotiations are currently at a standstill. The latest Russian proposal was unacceptable to Ukraine. Yet Putin seems to push for diplomacy. What is your assessment of the current military and diplomatic situation?

Negotiations during wartime make sense, but any talks this year are unlikely to produce results. The two sides are too far apart. Ukraine urgently needs peace – but not at any price. It must be sustainable, which means either greater strength or solid security guarantees. So far, we’ve seen neither – from Russia nor the West. Putin only understands the language of strength and power. Right now, he sees Ukraine as weak, Europe as weak, and the West as further weakened by Trump’s influence. That emboldens him to keep pressing, to keep squeezing Ukraine for more territory. Until Ukraine’s position is significantly reinforced, sustainable peace will remain out of reach.

What would those peace guarantees look like?

We need to act on two levels: short-term and long-term. This is a war of attrition – it comes down to resources. No matter how determined we are, Ukraine cannot win alone against a Russia that has three to four times more resources. But with Western backing, Russia stands no chance. Its GDP equals that of Italy – not of the EU or the United States.

To resist Putin effectively, Ukraine must begin developing its own military-industrial capacity on the ground. That’s the key short-term goal: to produce weapons and defense systems inside Ukraine rather than relying entirely on foreign supplies. But to make that possible, we need protection from the air. At least part of the country – ideally the western regions – must be shielded from Russian rockets and drones. These areas could serve as economic and logistical bases, essential for sustaining the war effort. Without air coverage, however, anything we build could be destroyed.

This is not a new idea. It has been echoed by President Zelensky, supported by British PM Keir Starmer, and discussed by leaders like Olaf Scholz and Emmanuel Macron. It’s often referred to as the “coalition of the willing” or the “Danish model.” The Danish model does not mean simply receiving weapons from the EU – it means building Ukraine’s own defense industry with European funding. This would be both more cost-effective and more sustainable.

And in the long term?

In the long term, what matters most is that the West – however defined, regardless of America’s role – must evolve into a union that is not only political and economic, but also a true security community. This new configuration could take many forms: NATO, a reconfigured European Union, or perhaps a smaller alliance that includes parts of the EU and Britain. Its final shape will depend on how the war ends.

From our perspective, Ukraine is not a problem, but an asset. It has now the largest army in Europe, and it has proven relatively effective against a much larger Russian force. More importantly, it has real battlefield experience – something no other European country can claim.

Do you believe Trump will help you?

Not much. The more we come to know Trump, the less hope we have. There’s a saying going around that he’s a sheep in a wolf’s clothing – tough with the weak, weak with the strong. So far, he’s shown a soft stance toward both Putin and Netanyahu. And since he (wrongly) sees Ukraine as weak, he believes he can do whatever he wants – which likely means abandoning us.

The biggest unknown now is whether European aid can replace American support. That’s being discussed, but we don’t yet have a definitive answer.

What’s your assessment on this issue?

There are two things that are truly indispensable to Ukraine. First, the Patriot air defense systems –which only the U.S. or European countries like Germany, who produce them, can provide. But the U.S. would have to authorize their delivery. Second, and just as crucial, is satellite intelligence. If those two needs are met, we believe the rest – equipment, supplies, even weapon production – could be covered either through European support or our own industrial capacity.

For now, we believe we have the resources to continue fighting until the end of this year, maybe even into the next. But beyond that, no one knows.

What is the current state of Ukrainian public opinion?

Ukrainians want the war to end. That’s clear. The major shift we’ve seen recently is the growing realization that this war could go on for a long time. There may be negotiations or even a truce, but as long as Putin remains in power – as he’s obsessed with Ukraine – the threat will persist, whether the war is hot, cold, or hybrid.

People are exhausted. We want the war to stop. But not on just any terms: there can be no settlement that legitimizes Russian control over Crimea or Donbas under international law. We believe Putin’s regime will eventually collapse. Until then, we might temporarily accept some occupied territories – but never legally recognize them.

Putin wants to see a change of leadership in Kyiv. If elections were held today, would Zelensky still win?

Yes, without a doubt – against any candidate but one. That one exception is General Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the former commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. He’s extremely popular – more popular than Zelensky – but it’s unclear whether he plans to enter politics. For now, he’s serving as ambassador to the UK.

But aside from that, Zelensky would beat any other candidate. That said, it’s not really about who would win. Ukrainians don’t want elections during the war. They see it as suicidal. Yes, they want elections eventually, and likely a renewal of the country’s political elite – but only after peace, not before.

What’s Zelensky’s current level of support?

There’s a strong public consensus: holding elections during wartime would divide the country, weaken the war effort, and risk internal instability – none of which Ukraine can afford. Zelensky is fulfilling his role. He is Ukraine, but Ukraine is not Zelensky. While public opinion is mixed, he still enjoys broad support on the fundamental issues.

What’s less certain is whether he wants to run again. After more than three years as a wartime president, working around the clock, he must be physically and emotionally exhausted. There’s a saying going around: Zelensky is playing the role of Churchill. And what happened to Churchill after the war? He lost the election. We wish Zelensky to lead Ukraine successfully through the war, not to be the president of peace.

In a previous interview, you said that returning to Ukraine’s 1991 borders is now unrealistic. What kind of compromise might Ukraine accept – without sacrificing its sovereignty?

The biggest change in public thinking over the past year is this: nowadays Ukrainians realize that even returning to the 2022 borders is no longer realistic. In one way or another we have to concede these territories, we don’t know how else it could be done.

There are currently three scenarios being debated in Ukraine. First, the Russian scenario – essentially capitulation. Ukraine would cede territory, accept a smaller army, and fall under Russian control. This is completely rejected by both the government and society. Second, the American scenario, largely associated with Trump. It would mean agreeing to a negotiated settlement that grants Crimea and Donbas to Russia with formal international recognition. Again, this is unacceptable to most Ukrainians. The third is the European scenario – a compromise in which Ukraine might temporarily accept that some territories are beyond its immediate control. But this would only be acceptable if accompanied by serious negotiations and, above all, strong guarantees.

Cover photo by Reset DOC.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).