This brief glimpse into the terrain of street art in Athens is a partial, subjective view of the emergent feelings aroused by the proliferation of marks, inscriptions and statements on the walls of the city. That it is so is because my interest, in this short piece, is to push beyond the connections—between tags and human rights; graffiti and identities; street art and subcultures; freedom of expression and the limits of criminality—toward an evokation of a poetics of political street art. In this sense, I am not interested in defining what street art is (what counts or does not count as street art) but what it does.

And I seek to know, in particular, what the function of street art is in a city in a time of crisis. As such, I am thinking about the ways street art is a kind of utterance—how, in its being-in-the-world, it renders public spaces into places (de Certeau, 1984). By relying on the initial notion of talking walls, I am invoking the power of paint, stencils, tags, and slogans to vocalise urban concerns.

A point of clarification: by political street art, I refer to a conceptual engagement with social issues in public space. With this in mind, this short article is not trying to assess the artistic quality of the artworks or provide definitions and genealogies of graffiti and street art. Rather, I examine how street art becomes the marker of an alternative voice in the city, in order to unpack the multiple social realities of a city in crisis. Thus, this is not an investigation of what constitutes political and apolitical street art in relation to aesthetic categories. Such analysis serves only to mark out ‘belonging’ in relation to artistic skill or technique.

Instead, I have highlighted practices that emphasise disturbance, since political street art has the capacity to disturb the hegemonic conventions of cityscapes. It is this notion of disturbance that is perhaps the most forceful argument for the value(s) inherent to the practice of street art in times of crisis—not least because the visual disruption of urban spaces documents, archives and reflects the milieu of growing inequalities, police brutality and social uncertainties in urban communities.

Political street art is connected to and inspired by the existing social reality. Athens is the canvas and social conditions the paint in an open gallery of untold stories. In this light, street artists are remapping the city by questioning what voices and stories can be represented in public space (Tsilimpounidi, 2015). Indeed, political street art has boomed in Athens over the last years, projecting marginal stories onto walls across the city. Public space has always been a terrain of tension and struggle for inclusion and recognition; political street art brings forth a liberating potential and the urban opportunities for playfulness.

Political street art manages to create a mirror where ‘we’—the public, the passers-by—can recognise the features of our own concerns. What is remarkable is the personal and at the same time deeply collective voice that emerges from the pieces. Moreover, the voice transmits an important message: the words as living bridges between the street artists and the urban populace attempt to disrupt and disturb the hegemonic monopoly on truth (Avramidis & Tsilimpounidi, 2017).

In this way, in Athens today everything that is not otherwise expressed in the mass media, thus efectively silenced and invisible, is being screamed out across city walls. Political street art opens a space of negotiation and dialogue in the existing social and political status quo—or more correctly, it tags a new space where margins have a voice. Unlike other resistant acts that attempt to dismantle power structures, street art does so much not attack material property, since walls are left standing; rather, it attacks the property relation, urging a redefinition of the relation of space to individual. Using public space as a surface for interaction and communication, artists create an alternative diary of their city. In what follows, we’ll engage with this alternative diary of Athens in the space of three blocks of the city centre.

‘Welcome to the civilization of fear’, Artist: NDA, Photographer: Author

‘Welcome to the Civilization of Fear’ announces a label above the picture of a genderless masked figure walking through the centre of Athens. The masked figure interacts with the passers-by, creating its own aesthetic trajectories in the city. The placing of the piece is also important, as it is found next to the university building of Athens’ Polytechneio, an ideologically charged space as the revolt against the military dictatorship started there in 1973.

In recent years, the building has remained a hub for gatherings and discussions by different groups, usually associated with radical left and anti-authoritarian movements. If you can see this piece, you are in the centre of Athens. If you are one of the tourists navigating Athens, you are probably on your way to visit the National Archaeological Museum, which is just two blocks away. So, this piece is the bittersweet welcome, or perhaps a warning of what you will encounter in the next block on your way to the museum. Most days, two large paddy wagons are parked in front of the museum, with at least 15 fully armed police officers in riot gear forming a small human wall hiding your view of the beautiful façade of the museum.

If you are lucky enough, you will also encounter the fully-geared, fully-armed officer responsible for terrorising anyone who approaches, pointing his semi-automatic weapon at the crowds walking by in the streets. Welcome to the civilization of fear; welcome to the new militarised zone of Athens; welcome to the spectacle of urban war. Now, I know you are just a happy tourist on your way to the museum, but please consider this: do you look different? Will you be profiled?

Please do not get alarmed, Athens is still one of the safest metropolises—it is all a spectacle. Gas-masked figures are a very familiar scene on this block, as students and members of the anti-authoritarian movement clash often with the riot police. These clashes produce notorious violations of human rights and excessive brutality, including use of grenades and teargas. Many residents of this neighborhood (Exarchia) keep a gas mask handy at home, since inhaling teargas is a usual (sometimes weekly) phenomenon in the street, or even inside their apartments.

Greek Police and Drug Dealing Sign, Artist: Unknown, Photographer: Author

Congratulations! If you are seeing this sign it means that you probably made it to the National Archaeological Museum—I hope you enjoyed it—and are now on your way to discover the nice coffee shops and street food in the neighborhood of Exarchia, which is where the museum is located. The fully-armed riot police officers are still visible, but you now leave them behind you as you walk on to the iconic building of the Polytechneio next to the museum. You turn the corner onto Stournari Street and you at the entrance gate of Polytechneio, where you will find yourself puzzled by this sign (image 2). The blue sign at the very top is there to inform us that this spot is reserved for people with disabilities.

‘Great!’ you think. The second, round, blue sign is more puzzling. It is the official logo of the Greek Police (in Greek letters). In the official version, the logo includes an olive branch (which is present in this version as well) and, in the centre, the symbol of the scales of justice. In this version, a syringe replaces the symbol of justice. This urban intervention seeks to criticise the notorious involvement of the Greek police with drug dealing mafia in the neighborhood. (see also)

The logo, using and subverting state symbols and aesthetics, is informing us that this is a zone of drug injections controlled by the Greek police. ‘This cannot be possible!’ you might exclaim. ‘I just saw so many fully armed riot police officers, who could, for sure, be able to deal with any problem concerning illegal activities.’ Yet, the ‘exchanges’ are taking place in daylight right next to them and they never seem to be alarmed, or even willing to do anything about it. In fact, if you stand at the same place for a while as you trying to make sense of the logo, someone might approach you and ask you ‘if you need something.’

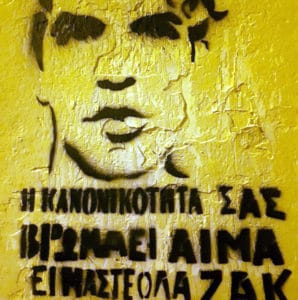

‘Your normativity reeks of blood’, Artist: unknown, Photographer: Author

I’m certain that you were able to relax a bit at Exarchia and are now heading towards Patision Street for a glimpse of the Acropolis. Three blocks away from Polytecheio, the streets are covered with this stencil of someone’s face and a tag in Greek that translates to ‘your normativity reeks of blood. We are all Zak’. This is the corner where the gay, HIV-positive human rights activist Zak Kostopoulos was murdered on Friday 21 September 2018. For many of us living in the city, time stopped on this corner. It was one of those events that divide the living history of an urban environment into a ‘before’ and an ‘after’.

After his murder, the spatial and social contract of the city broke forever for people who are not normative. Zak Kostopoulos was brutally murdered in broad daylight by two white, Greek straight men who were described as ‘good fathers and grandfathers’ protecting their properties in the mainstream media. Furthermore, Zak’s body was then beaten up by five police officers who are probably the one’s who gave the fatal struck (see also). Zak was murdered in front of the eyes of many civilians who happened to be there, it is the centre of a busy city after all, and did nothing to save him.

The Greek police arrested Zak and not his murderers; well, they would have to also arrest themselves I suppose. Zak also had an alter-ego, the drag persona Zackie Oh, and their body was murdered many times by the mainstream media that were trying to justify the murder by firstly calling Zak a dangerous thief, then a ‘junkie’ (sic), and a threat to public health, who could not be easily arrested by the police risking their life with his ‘queer illness.’ Of course, four months after Zak’s murder every allegation and accusation was proven to be false; but remember the scales of justice in the sign of the Greek police?

When enforced normativity takes place in a necropolitical regime of who deserves to be seen in public space, then we are all Zak. Athens screams through its walls a thousand stories, not all of them nice and gentile like the Western (colonial) narration of its glorious past. After all the oldest graffiti signs in the city were made on marble pillars, but not they are not called ‘acts of vandalism’ but, rather, traces of a ‘glorious ancient past’ kept in many museums around the globe.

References

– de Certeau, Michel (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

– Avramidis, Konstantinos & Tsilimpounidi, Myrto (eds.) (2017) Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City. London: Routledge.

– Tsilimpounidi, Myrto (2015) ‘‘If these walls could talk’: street art and urban belonging in the Athens of crisis’ Laboratorium: Russian Review of Social Research. Special Issue on Street Art and Graffiti. Vol. 7(2): 71–91.