It is certainly surprising that, in the middle of major international conflicts (such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the repeated massacres in Gaza, and the Israel–Iran war), the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) has not been able to play the role of mediation that the UN Charter contemplated. The UNSC has gathered daily, and its permanent and elected members have discussed both minor and major crises, but without being able to agree on any Resolution regarding the most important events. By itself, this would not have been a major change: in the Cold War, many UNSC Resolutions were blocked by either the USA or the USSR veto. For far too long, two major blocks operated in opposite directions: on one side, the liberal democracies led by France, the United Kingdom, and, above all, the United States, and on the opposite side, the Soviet Union – and later Russia – supported by China.

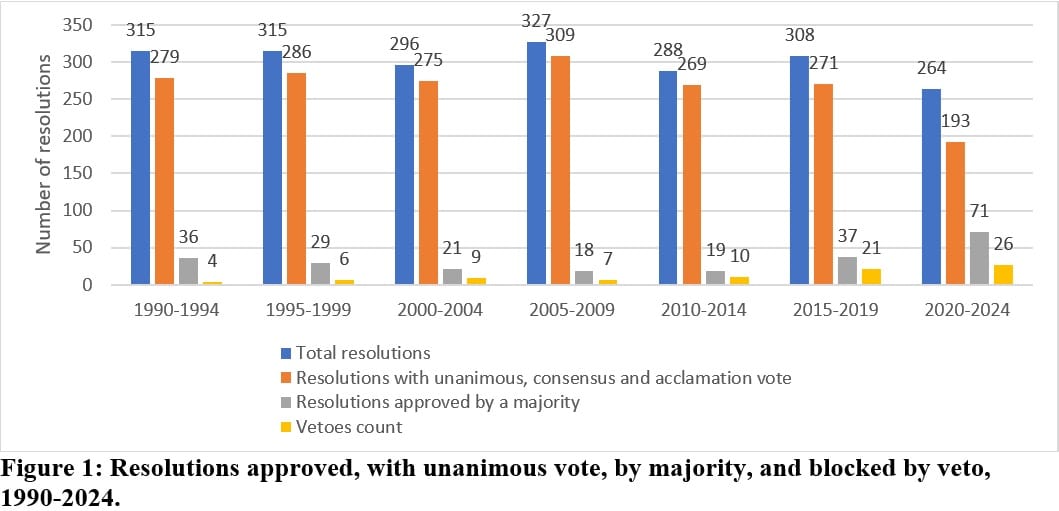

Could a different UNSC be more effective? For at least thirty years, there has been talk of a new enlargement of the UNSC, mainly aimed at making it more representative through the inclusion of new member states. States that want enlargement recall that entire continents, such as Africa and Latin America, have no permanent member, and the same goes for the most populous country in the world, India. But are we sure that enlargement will make the Security Council better equipped to contribute positively to peace and stability? Figure 1 reports the number of resolutions approved, those that have been approved even by unanimous vote, those that have been approved by majority, and those that have been blocked. It may be a surprise that in most cases, the UNSC reaches unanimity. The fact that, from a quantitative point of view, the rejected resolutions are only 5 percent, confirms that international rivalry is concentrated on a few issues.

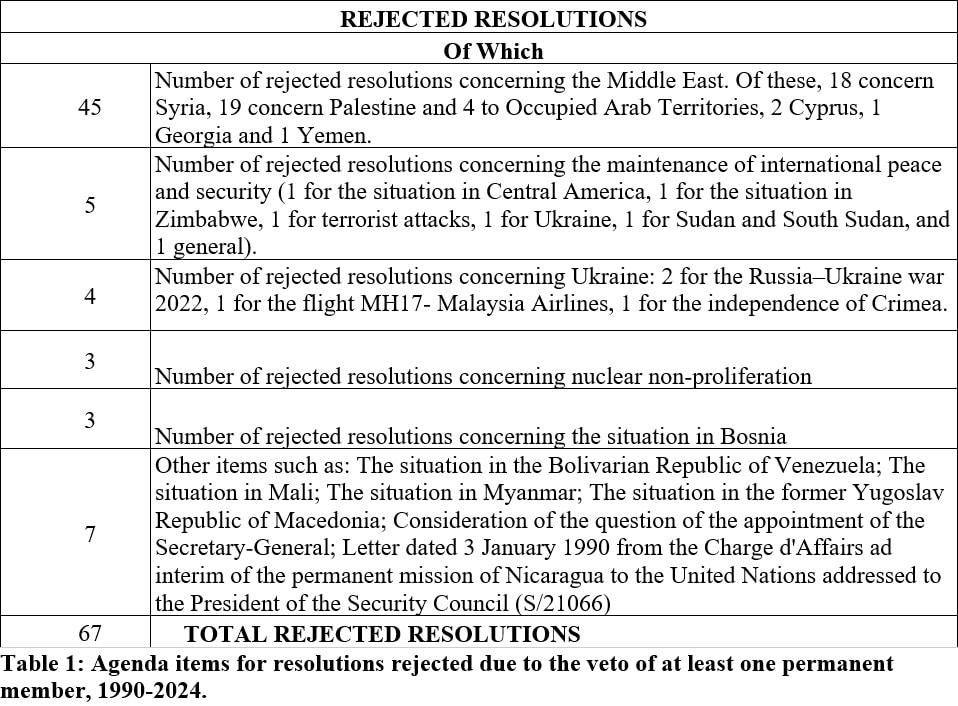

Of course, not all resolutions have an equal political weight. When resolutions are vetoed by one permanent member, it means that there are controversial issues that cannot be sorted out by mediation and compromise. Table 1 reports the issues on which resolutions have been vetoed

Since 1990, the veto patterns have been the following:

– The United States has vetoed mainly on resolutions concerning Israel and Palestine;

– Russia has used the veto to protect its interests in Syria and Ukraine;

– China, after a long period of disinterest, has only recently started to use its veto, and almost always in line with Russia;

– France and the United Kingdom have not used the veto since 1990.

Increasing the number of members of the UNSC – both elected and permanent – would not make the decision-making process easier if a single vote against by a permanent member is enough to block the passage of a resolution. Enlargement would perhaps make the UNSC more representative, but there is no indication that those who hold a seat are acting on behalf of their continent; on the contrary. Those who oppose India’s entry as a permanent member are mainly Pakistan, and the same goes for Brazil and Argentina, Japan, and China, and so on.

It would be much more useful to expand the UNSC to include regional organizations, even if only with an advisory vote. If the European Union, ASEAN, Mercosur, the Organization of African States, the Arab League, and others were allowed to be in the Council room, they could hopefully make the body more representative, allowing regional organizations to act as moderators. States would be encouraged to increase coordination on a regional basis, thereby contributing to collective security.

If the efficiency and authority of the UNSC are due to the veto power of the permanent members, the problem cannot be solved with enlargement but rather by introducing mechanisms able to limit its use and make it politically more costly. Proposed measures include:

– Thematic limitations, preventing its use in cases of crimes against humanity, genocide, and other serious violations of international law;

– Making the veto valid only if at least one other state joins the permanent member in opposing the resolution;

– Requiring the state exercising the veto to justify its decision before the General Assembly. Although this measure is not binding, it aims to increase the reputational cost of using the veto;

– Invalidating the veto of a permanent member when there is a qualified majority against it in the General Assembly.

At present, the possibility of reducing — and eventually eliminating — the P5 veto power remains aspirational and can only be achieved if the P5 themselves choose not to exercise it. However, it is increasingly anachronistic that the most important decisions are made by a small number of governments. As a result, the UN is not equipped with the necessary tools to peacefully resolve conflicts. The adage goes: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. But in the case of the Security Council, one should instead say: yes, it’s broken, but better flawed than scrapped.

Cover photo: United Nations Security Council is held at the United Nations Headquarters in New York on September 24, 2024. (Photo by Yasushi Kaneko / The Yomiuri Shimbun via AFP)

This evidence reported in this article is based on Daniele Archibugi, Marco Cellini and Azzurra Malgieri, “The Reform of the UN Security Council: What Are the Issues” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 31(2), 137-162, https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-03102003.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).