There are two main challenges in assessing the legacy of the Gezi Park protests after five years. First, we should keep in mind the event remains very much “of the present” at least in so far as its impact is still being felt, not least because it has changed the paradigm of social protest and resistance in Turkey radically.

Moreover, what caused it and its long-term impact remain the subject of ongoing debate. Whatever we have to say about Gezi today, then, may offer only partial or tentative conclusions on the dynamics of the event. Related to this, analysts face a second challenge—namely, that like all social movements of historical import, Gezi functions as a point of reference for protest groups seeking to challenge the status quo and the authorities seeking to forestall further eruptions.

For these reasons, the Gezi Park protests can only be properly understood when we consider how the regime and its supporters in Turkey have sought to “inoculate” themselves against the protests’ effects in the five years since. Indeed, that the Turkish authorities themselves consider Gezi such a focal point is one of the main reasons that this social movement retains its importance for Turkey.

In other words, five years after the Gezi protests, it is as necessary to focus on how Gezi has influenced the regime and the social forces arrayed around it as how it as impacted civil society more generally. In this text, I would thus like to follow the question of what has happened to “the rest”—namely pro-government social forces and the government itself—after the Gezi Park protests.

The burgeoning literature about Gezi mainly concentrates on what triggered the protests in the first place (including what prompted the protesters into action), the tremendous effect the protests had on the body politic and the public (re-)production of the Gezi events (including all artistic outputs) since. In the present contribution, by stressing the importance of the changes in other fields, I will limit myself to a discussion of the artistic and cultural arenas and try to investigate how protesters and the regime have produced their own visualities in the post-Gezi era.

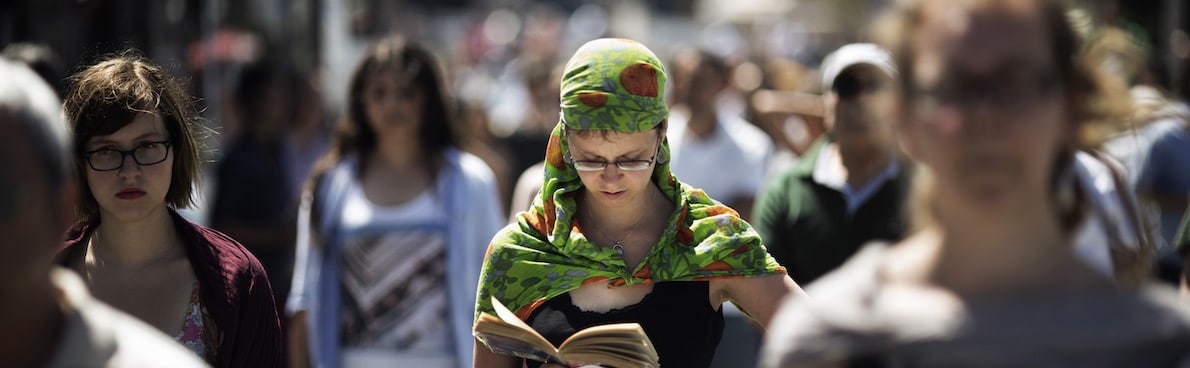

Street art of a social movement

The former is easier to describe. Street writings, performances, compositions, graffiti, in short, all of them are still in our memory, and in fact, it is through these productions that we are able to recall Gezi. Therefore, when we look back from today, what is called “the spirit of Gezi” has been stored in our memories and conveyed to others through these symbols, graffiti, music, dances etc. This is a kind of alternative memorialization and narration of the events shared by people who experienced Gezi in the streets. Although the official discourse plays all the angles to manipulate the outcomes of the protests and erases all of their physical marks from cities, artistic productions of the protests have morphed into codes that can be deciphered by people who were involved at the time.

Hence, street art of a social movement in the widest sense, namely any form of art made on the street as a place, gains the status of having “been there” even after it is destroyed. On the other hand, the effect of street art is crucial in foregrounding the historical weakness of the Turkish state apparatuses in the cultural and artistic spheres. For this very reason, state apparatuses and power elites have attempted to use humor and art much more in the post-Gezi era.

The first example I want to discuss is a set of performances that occurred in Taksim Square in 2013: the well-known Standing Man (Duran Adam) performance and the far less well-known counter-performance “Man Standing Against the Standing Man” (Duran Adama Karşı Duran Adam). On June 17, 2013, the artist Erdem Gündüz stood silently for eight hours in the square, facing the Atatürk Cultural Center (AKM), which had been scheduled for demolition. After some time, others joined Gündüz in the performance.

This collective stasis in an era of global mobility was highly effective and thought-provoking—triggering a (re-) examination of current events, and shifting attention from the war of words with the government to contemplate the massive violence that had occurred during the protests. People in other cities in Turkey also engaged the same form of action: stopping, observing and contemplating. In the face of such a clever example of effective act of civil disobedience, police vacilated over what to do, since standing in a public sphere is not a defined crime.

Man Standing Against the Standing Man

A response to Standing Man came two days later. This counter-performance would pave the way for “disproportionate intelligence” (orantısız zeka), a phrase that was widely used during the time of the protests.

Eight men wearing t-shirts bearing the phrase “Man Standing Against the Standing Man” appeared amidst those in the square who had been keeping the original performance going. After milling around for about half an hour, the men, with 20–25 people gathered behind them, dispersed but not before making the following short statement: “We have delivered our message; now we’re going. Our goal is not to close roads”.i

This “performance” could also be read as a visual representation of the statement made by Erdogan during the protests: “There is another 50 percent [that voted for the AKP (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi—Justice and Development Party)] that we are having difficulty keeping at home”. It was also crucial in terms of representing the weakness of government in asserting hegemonic power in the Gramscian sense in the fields of art and culture in Turkey. Moreover, it can also be seen as a visual indicator of the more authoritarian policies that have been in effect in Turkey since the Gezi protests.

After the Gezi protests, the authoritarian tendencies of the government heightened and as a result, both discursive and operational rigidities came to be seen more often. The criminalization of individuals and groups also allowed the AKP to represent itself as the only actor in the democratic arena. In other words, while criminalizing others, the AKP also attempted to absolve itself from the charges of state violence and human rights violations presented against it. But this effort had to be supported by a new visual culture and identity construction. Although this process of identity construction had been in progress for some time before the Gezi protests, it has since accelerated and widened.

Purify the modern Turkey of its Kemalist origins

Indeed, I think in recent years this process has progressed in two ways. The first has been the destruction or removal of certain Kemalist monuments, architectural works, symbols, etc. which can be conceptualized as national images, or following Lauren Berlant, the collective “National Symbolic” that symbolizes the visual presence of the state.ii

The goal here is to purify the image of the modern Turkish state of its Kemalist origins and to foreground other historical reference points. Yet, since the current government has no issue with symbols related to Turkishness inherited from the pre-AKP past, some of these symbols have assumed new prominence in the public square. The demolition of the AKM, the Artillery Barracks project and the new mosque under construction in Taksim Square are cases in point. Similarly, construction of the Ankara city gates with their Seljuk and Ottoman architecture, the design of new government offices, references to old Turkic states in official ceremonies, annual celebrations of the 1453 Conquest of Istanbul, the support given to certain television programs, such as Diriliş Ertuğrul (Resurrection of Ertugrul), can be evaluated under this category.

The second involves combatting the regime’s obvious inadequacies in the fields of art and humor, which became apparent during the Gezi Park protests. One of the most prominent examples of this is the emergence of magazines such as Cafcaf, Misvak, Cins, Hacamat, Post-öykü and İzdiham against the circulation of cartoon and popular culture magazines due to the widespread use of the internet during protests.iii

Another striking example is the Yeditepe Biennial, which was launched this year. In contrast to the Istanbul Biennial, the Yeditepe Biennial concentrates on traditional Ottoman–Turkic art forms such as ebru (paper marbling), hat sanatı (calligraphy), tezhip (ornamentation), minyatür (miniature-making) etc. It is supported primarily by the office of the president, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the Fatih Municipality in Istanbul. Mustafa Demir, the chair of the board of the biennial, which kicked off with the motto “You have an art!”, gave the following statement to Yeni Şafak newspaper:

From now on, we can also treat the Yeditepe Biennial as robust and weighty enough to represent the ancient culture of Turkey in international biennials. For example, if there will be a Turkish pavilion at the Venice Biennial, I am sure that, after 2018 and 2020, Yeditepe will be taken into consideration. This is not my personal position [but that of many other commentators].iv

The Istanbul Biennal

The Istanbul Biennial, which the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV) has organized since 1987, is Turkey’s largest contemporary art event. IKSV is also responsible for preparing the Turkish pavilion at the Venice Biennale. As is well known, the Venice Biennale—an annual art exhibit that begain in 1895—is divided into national pavilions. This image-change of the country is not related to a personal claim, as stated by Demir, but to a conscious cultural policy change that the AKP has been unfolding since it came to power in 2002.

This attempt for change can also be read in some parts of the AKP’s 2015 election manifesto under the section “Culture and Art”. Here are few examples:

- We will give weight to our social and cultural assessments to be examined in detail in educational institutions in order to strengthen social unity and the sense of identity and belonging.

- We will take measures to ensure that the Turkish film industry is among the leading industries in the world. We will establish an effective working mechanism for processing our national, religious, moral and folkloric values that are the basic elements of our culture.

- We will support and promote the transcription of important personalities and events of our history and fairy tale heroes into documentaries, TV series and cartoons.

- We will continue to sustain and popularize our vakıf (foundation) tradition as the institutional transmitter of our civilizational values.

- We will ensure the effective teaching of the Ottoman–Turkish language, which is one of the most important elements of our civilization, and strengthen the connection with our history and culture.v

The Gezi Park trials have been reawakening in recent days. Although the link between these awakenings and the upcoming municipal elections is clear, considering the Gezi protests as an important and effective point of reference for government in the process of constructing a new identity should also be brought into the equation. Yet, “the rest” still seems far from being hegemonic—let alone dominant—in Turkey’s art and culture scene.

Notes

ii Lauren Berlant, The Anatomy of National Fantasy: Hawthorne, Utopia and Everyday Life, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

iii For a detailed analysis of Islamic humor magazine publishing in Turkey, see Erdem Çolak, “İslam ile Görsel Mizah: Türkiye’de İslami Mizah Dergiciliğinin Dönüşümünün Bir Eleştirisi” (Islam and Visual Humor: A Critic of the Transformation of the Islamic Humour Magazine Publishing in Turkey), Moment: Journal of Cultural Studies, Faculty of Communication, Hacettepe University 3(1), (2016), 228–247 (In Turkish).

Photo: MARCO LONGARI / AFP