The new world order being precipitated by the Putin regime’s invasion of Ukraine and the NATO-led response is not the new world order that China hoped for, even though China has been promoting an alternative model to the existing world order. A geoeconomic power shift has occurred and the global landscape emerging from it represented the end of five hundred years of “Western” dominance, but the US and EU response to the war in Ukraine seems to be offering the US, through NATO, an opportunity to re-forge a world order subordinated to US leadership and interests, even though uncertainty about the constancy and reliability of the US as a world leader (NATO’s point of view) or a hegemonic power (the point of view of Russia and China and developing countries) have eroded America’s moral authority in world affairs. “America First” and neo-isolationism could return to power and the current opposition party flirts with and even endorses populist nationalism and white supremacy, defending a right-wing insurrection as “normal political discourse”.

At the same time, Vladimir Putin’s return to a nineteenth century “Great Powers” vision of the world order as a response to NATO’s abandonment of the “Yalta Agreement” that cemented a post-World War II order is not the alternative that China wants. The NATO point of view seems to be shaped by “presentism” instead of the longue durée. The Cold War facilitated a binary and simplistic strategy of “us versus them” between a “free world” and a “communist bloc”. Modern history has shown that the victors’ treatment of the defeated often established the bases for new wars. The “victors” in the Cold War could have treated Russia (the “defeated” USSR) differently. Instead, they seem to have oscillated between wanting to see China as the new binary foe or maintaining Russia in the role of the USSR.

History and geography give more perspective on these matters. Russia has always craved access to warm water ports without impediments. The Crimea and southern Ukraine give access to the Black Sea, but Turkey, a NATO member, controls the Bosporus. Kaliningrad gives access to the Baltic Sea but is isolated from Russia inside EU and NATO territory. From Putin’s point of view, this was not a problem when Belarus and the Baltic States were Soviet territory, but it is now. The Arctic is melting, and an open Arctic Ocean may become a new focus of conflict.

Russia has historically considered itself to be European, even though most of its territory is in Asia. China wants to construct a Euroasiatic order through its Belt and Road Initiative. Europeans and Asians seemed to be converging across the Eurasian land mass for which the BRI promises an inevitable flood of investment that will create a flourishing Eurasian commercial system, but the war in Ukraine and the sanctions that the US proposes against Russia will impede this process, to the annoyance of potential beneficiaries.

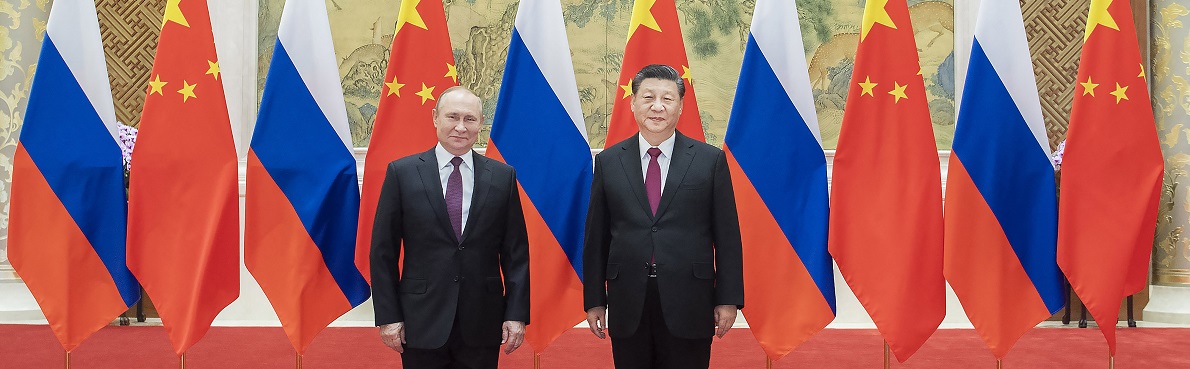

For China, economic integration is a more effective motor of long-term political change than is a short-term policy of sanctions, or war. Russia is nervous about China, but isolation of Russia will force a closer alliance between the two countries. It is curious that the US under Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon could see the possibility of cultivating cooperation with China s a means to offsetting the USSR, but current US strategists do not. Despite their joint statements of “limitless friendship”, relations between Russia and China have historically been difficult. China will not take kindly to attempts to enforce sanctions on Russian raw materials that are crucial to China’s development. Although the joint statement goes out of its way to criticise attempts by “certain States” to “impose their own ‘democratic standards’ on other countries”, to “monopolize the right to assess the level of compliance with democratic criteria”, and to “draw dividing lines based on the grounds of ideology … by establishing exclusive blocs and alliances of convenience”, China wants to maintain a rules-based world order conducive to trade. This is another reason why China cannot endorse Russia’s actions: they are provoking global economic shocks that are highly unwelcome. The joint statement concludes, “Such attempts at hegemony pose serious threats to global and regional peace and stability and undermine the stability of the world order”. Ironically, it is Russia that has taken steps that undermine the stability of world order, and Russia may have thought it could count on Chinese support.

The hybrid warfare of the twenty-first century “weaponises” almost all aspects of ordinary social life, from trade to the internet. The war in Ukraine could bring about a major shift in the direction of supply chains that may come to be called hostile as well. Russia preferred to sell its natural gas to Europe but could just as well sell it to China, Japan and South Korea, though not as easily; the necessary infrastructure is lacking at present because Russia prioritised Europe. The US calls upon Europe to boycott Russian gas because it creates dependency, offering instead dependency on US liquefied gas. China’s Euroasiatic initiative opts for trade and commerce as the means to maintain a peaceful and stable world order, rather than expansionism and military dominance. China offers a win-win situation, the creation of an economic interdependence based on equality, mutual respect and mutual profit. China wins in this situation, but so do its partners.

A joint statement issued by China and Russia before the invasion proposed to “strongly uphold the outcomes of the Second World War and the existing post-war world order”. The Cold War froze in place one aspect of that outcome — the Yalta agreement. The fall of the USSR eroded that example of Realpolitik. The Warsaw Pact disappeared but NATO expanded. China is a nervous observer of this process. NATO’s perception of its sphere of interest runs from Vancouver to Vladivostok and it contemplates the accession of Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea to a North Atlantic pact that has intervened in wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria. It is not hard to see in the development of NATO post-Cold War an ambition to create a worldwide alliance dominated by the USA. It is also not hard to see that such an alliance would contain rather than include Russia or China, giving both countries reason for concern. The presence of US missile systems in Eastern Europe and East Asia, as well as the AUKUS agreement between Australia, the US and the UK, and US withdrawal from disarmament treaties, all lend credence to this concern. None of this justifies the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but it does help to contextualise China’s response to the invasion.

The joint statement also proposes to “resist attempts to deny, distort, and falsify the history of the Second World War”, to “protect the United Nations-driven international architecture and the international law-based world order, seek genuine multipolarity” and to “promote more democratic international relations, and ensure peace, stability and sustainable development across the world”. Implicit in this catalogue is a criticism of a world order dominated in the voting systems of the Bretton Woods institutions by the USA and Western Europe, and the elevation of the losing WWII enemies — Germany and Japan — to the status of NATO allies at the cost of the winning allies — then the USSR and the Republic of China, now Russia and the PRC. More important is the insistence on “genuine multipolarity”, “more democratic international relations” and the right to “sustainable development”, a right claimed by the rest of the developing world as well.

China cannot endorse what Russia has done because sovereignty and territorial integrity are primordial in Chinese foreign policy and Ukraine is a strategic partner for China in terms of raw materials. China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity were repeatedly violated by imperialist aggression from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries by powers that were jealous of their own sovereignty at home. From the point of view of the PRC, sovereignty will not be fully restored, nor can China truly be equal to the former imperialist powers in the concert of nations until Taiwan is reintegrated into China, with no new loss of territory. Russia has acted militarily with impunity in Chechnya, Georgia and the Crimea in recent times, all in the name of “historical” sovereignty and territorial integrity. Such impunity might encourage Chinese strategists to think that Taiwan could also be “recovered” militarily with impunity, a right that China has reserved for itself in law, but not yet acted upon.

The invasion of Ukraine is a different matter. It is a clear violation of sovereignty and territorial integrity that China cannot justify nor defend. Nor can China align itself with a US-dominated NATO that it sees as an instrument of US hegemony. The situation is fluid, but China is trying to maintain an equidistant stance and would prefer a return to a pacific rules-based world order founded on a balance of power that favours neither NATO nor Russia. Hence China’s agreement with Russian opposition to NATO’s expansion, but not with Russia’s actions. China has abstained on UN resolutions critical of Russia that it could have vetoed and has offered to act as a mediator in the conflict. Such a stance is probably more in tune with the attitude of the rest of what was once called the Third World, that is to say, the largest part of the world’s population — as long as China itself does not exhibit hegemonic tendencies.

China advocates a different world order, a “China Model” that would return China to the pre-eminent position it held in the world before succumbing to Western aggression in the nineteenth century. It would improve the people’s standard of living and allow China to take centre stage in world affairs, all under an efficient technocratic enlightened or “benevolent” Party-State. This model would be an alternative to neo-liberalism in the emerging world order as well as a political alternative to the liberal democracy of “the West”. China’s successful development model resists the neoliberal Washington Consensus, and both the success and the resistance lend China soft power in the eyes of “the Rest”. For the time being, China advocates a diverse and multipolar world as an alternative to US/NATO hegemony —a balance of power among large regional blocks that would prevent any single one of them from dominating the emerging world order.

In an emerging world order with liberal democracy in crisis due to its failure to guarantee equality, China’s technocratic efficiency in promoting social equity, as well as China’s defence of multipolarity, might have been gaining ground as competitive alternative paradigms — seriously challenging the premise that liberal representative democracy is necessarily the final step in the evolution of the governance of complex societies on a global scale. It remains to be seen whether Putin’s short-range brutality in Ukraine gives an impetus to America’s attempt to marshal a unified response by the world’s “democracies” against “authoritarianism” that can short circuit China’s long-range plan to pacifically re-orientate the existing world order.

References

Golden, Sean, “A ‘China Model’ for the ‘New Era’”, CIDOB Opinion, October 2017

Golden, Seán (2018) ‘New Paradigms for the New Silk Road’, in Carmen Mendes (ed.), China’s New Silk Road. An Emerging World Order, London: Routledge, 2018, 7-20.

Golden, Sean, “The US and China in the new global order”, CIDOB Opinion, January 2020

Cover Photo: Chinese President Xi Jinping holds talks with Russian President Vladimir Putin ahead of the Winter Olympics opening – Beijing, 4 February 2022 (Li Tao / Xinhua via AFP).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.