Turkey was one of the nations most taken by surprise by the overwhelming storming of Kabul, just as it was involved in trying to reach an agreement with the U.S. to assume responsibility for the protection and management of the Hamid Karzai international airport once the international coalition had completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan. Kabul’s international airport is the country’s only gateway. Since August 31st it has not been operational and cannot yet be fully used for any form of transport. This makes it impossible for commercial airlines to resume flights to Kabul, further increasing the city’s isolation.

The Taliban have asked Ankara and Doha to provide technical assistance in managing the airport and talks are still ongoing to try and reach an agreement on how the airport could be reopened in a safe and efficient manner. Unlike many Western countries and NATO, Turkey has decided to keep its embassy in Kabul open to maintain communication channels with the new government, however, managing the airport without a solid security organisation is quite another matter. In fact, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan recently declared that managing the airport without an adequate Turkish military presence on the ground could not take place in a secure setting. But the Taliban do not want even one Turkish soldier in the country and has allegedly given three conditions: recognition of the new regime in Kabul, management of the airport in a consortium created between Turkey and Qatar and that Ankara should not deploy a single soldier using only private security.The Turkish leader, however, is extremely prudent as far as these issues are concerned; he does not trust them since the operation presents high levels of risk. If not adequately protected, his technical staff could be targeted by jihadist extremists and that is why he would like to use his own army or private police forces such as the famous SADAT, already operating in Libya and Syria. Furthermore, Turkey’s requests for an inclusive government remain a sine qua non condition for long-term cooperation with the Taliban.

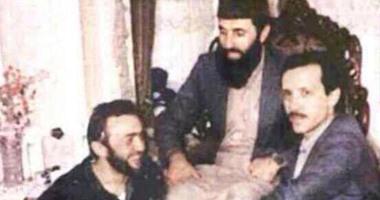

In 2015, with about 600 soldiers, Ankara assumed the task of guaranteeing security at Kabul’s airport within the framework of the NATO mission and would have liked to continue its military presence in order to protect its political and commercial interests in the region. Turkey therefore appeared ready to recognise the Taliban regime hoping that the new government would include people close to the Turkish president such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the former Afghan prime minister (1993-94 & 1996-97) who had expressed his approval for a temporary inclusive government. Erdoğan’s bond with Hekmatyar dates to the 1980s when he was a mujaheddin leader fighting against Soviet occupation. In recent days a photograph has circulated on social media portraying a very young Erdoğan seated next to Hekmatyar.

Another leader close to the Turkish president is Salahuddin Rabbani, head of the Jamaat-e Islami party, Afghanistan’s former Foreign Minister and ambassador to Turkey, one of the mediators appointed for the renewal of peace talks that should have been held in Istanbul.

Many wonder why Afghanistan has suddenly become one of the main issues on Turkey’s political agenda, while it was hardly mentioned until a few months ago. Some ask themselves why Turkey wishes to assume a high-profile role in the central-Asian country in spite of the obvious risks this would involve. The reasons lie both in the country’s current foreign policy strategy and in the need for the Turkish president to ensure his own political survival and that of his party. In recent years Ankara has seriously damaged its links with the United States and the European Union and now seems to wish to exploit the Afghan crisis claiming the role of peacemaker, a mediator between the Taliban and global powers, to prove its importance to the West and strengthen its international legitimacy, gaining prestige also at home where the Turkish president’s leadership is increasingly tarnished with consensus constantly falling. So, the Turkish leader is playing the Afghan card to consolidate his position in negotiations concerning other thorny issues with his historical allies. On the one hand with the United States so as to avoid further sanctions for buying the Russian S-400 anti-missile system and with the European Union as regards the disagreement with Greece and Cyprus concerning maritime borders, as well as issues concerning refugees and the deterioration of the rule of law and fundamental human rights in Turkey.

The other reason concerns domestic policy. The Turkish leader is increasingly losing approval in the polls and intends to pander to the ultra-nationalist and Turanist circles that could abandon him and that in his governing alliance are currently pushing for the adoption of a Eurasian doctrine that envisages Turkey reorienting itself away from the West, looking to Russia and China and the hinterland of Central and East Asia where the historical and cultural roots of Turkishness are to be found. There is now doubt that there are also economic reasons for the efforts made by Ankara to strengthen its role in Afghanistan, while waiting for great construction and infrastructure projects to be started in this country devastated by war. But Erdoğan’s calculations in his determination to fill the void left by the Americans, just like Russia and China are doing, could turn out to be fatal both for his power at home and in the region as well as in crisis areas where Turkey is militarily involved such as Syria and Libya.

The greatest risk posed by a possible agreement with the Taliban lies above all in the fact that the military and political victory achieved by the fundamentalist rebels in Afghanistan might reawaken and inspire the extremist Salafist and jihadist networks in the north of Syria where most of the territory is controlled by Turkey. Furthermore, there are a number of Turkish jihadist fighters and people with links to Ankara among the extremists that the Taliban released from Afghan prisons as they regained control over the country. It is very probable that they would prefer to return to Turkey or travel to northern Syria. Although there are strong ideological and ethnic divisions between the Taliban and the extremist Salafist jihadists in northern Syria, the return to power of the extremists brings back the spectre of a new jihadist route winding through Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Turkey.

Erdoğan is aware therefore that there are many arguments against his intention to reach agreements with the Taliban. He knows too well that Afghanistan reawakens memories of an Ottoman past for Turkey and that in truth most Turks reject this not only from a secular perspective but also from a religious one. If one glances at social media, one can see that many Turks of various social and pollical backgrounds are saying that the Taliban have religious ideas that are very distant from those of the Turks, and this has also been confirmed by many polls confirming the Turks’ opposition to any agreements with the Taliban. Furthermore, there is widespread opposition to immigration in the country, especially coming from the Middle East. Tukey is hosting about 3.7 million Syrians and over 300,000 registered Afghan refugees and if one were to add the assumed number of illegal immigrants, that number would rise to 500,000 and this Afghan presence is perceived transversally by the population as a threat. The significant dip in Erdoğan’s approval rating during of the month August was mainly the result of bad management of the emergency caused by fires that devastated vast areas in the country but was also linked to the immigration issue though for the moment there has not been a massive wave of immigrants but only widespread concern.

Furthermore, Erdoğan wishes to appear to be indispensable to NATO; he wants to prove he is a vital ally capable of ‘feeling building’ with Muslim countries and therefore playing a positive role as a mediator in relations with countries in the Middle East and Central Asia. He sees the Afghan crisis as an opportunity for regaining a central role in relations with the U.S. and the EU, a role that in recent months he has certainly lost. It is no coincidence that for now Erdoğan and Biden have only met thanks to Afghanistan and had it not been for the Afghan crisis Biden would probably have ignored Turkey for many more months.And the same applies to Germany, whose Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas, travelled to Turkey to discuss Afghanistan and otherwise most probably would not have gone. Ankara now appears to have re-entered the agendas of Western powers thanks to Afghanistan and the consequent threat of a new wave of migrants. The Turkish president therefore wishes to exploit this opportunity even if Kabul is not particularly important, per se, as far as his strategy is concerned.

Cover Photo: Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu delivers his comments on the recent Taliban takeover of Afghanistan – Amman, August 17, 2021 (AFP).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.