At every election in Poland, the electoral map throws the country’s historical partisan cleavage into sharp relief. Western regions and the large urban centres usually express a liberal–progressive choice while the east and the rural areas—usually poorer and closer to conservative values—place their trust in right-wing parties.

The parliamentary election held in October 2015 proved to be an exception. Poland’s main right-wing party, Law and Justice (PiS) won practically everywhere, even in the traditional strongholds of the Civic Platform (PO), the liberal party that had governed since 2007. It was a major triumph that resulted in an absolute majority of seats in parliament.

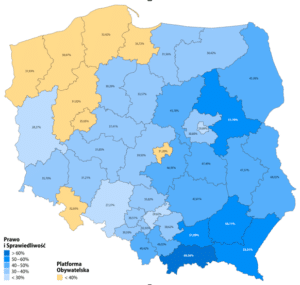

2015 elections | Results for the Sejm, the Polish parliament’s Lower House.

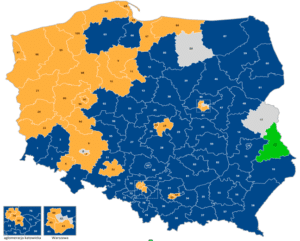

2015 elections | Results for the Senaye, the Polish parliament’s UpperHouse

There were various reasons for the 2015 change of direction, among them the crisis experienced by liberals. First and foremost, they were deprived of former premier Donald Tusk’s charismatic leadership (he had taken up office as president of the European Council in 2014).

But they were also devoid of new ideas after two terms in government and had their credibility undermined by a wiretapping scandal that revealed MPs discussing state affairs as if seated in a pub. The liberals thus left the door wide open for Jaroslaw Kaczynski, leader of the PiS and the twin brother of the former president Lech—killed with many other leading state officials in a tragic plane crash in Smolensk, Russia in 2010.

Jaroslaw Kaczynski, on the other hand, sensed that the pillars of “Sovereignty”, such as anti-elitism and a harsh “no” to migrants, would be rewarded by voters. Thus, he adapted his conservative and nationalist party message to these new trends by radicalising it.

There was, however, another factor that was perhaps even more decisive in ensuring the PIS’ triumph: the economy. The transition from Communism’s planned system to a free market was quite a success story for Poland. Since 1989, the country has experienced sustained annual GDP growth of around 4%. Almost uniquely in Europe, Poland also escaped a downturn after the 2008–09 financial crisis.

EU membership in 2004 consolidated the country’s foundations and the subsequent figures for trade volume growth are extraordinary. In 2004, exports amounted to 60 billion euros and are now over 200 billion. During the same period, unemployment fell from 19% to 5-6%. Turning to infrastructure, it is noteworthy that there are over 1,500 kilometres of motorways today in Poland, compared to the 400 kilometres that existed fifteen years ago. Furthermore, as mentioned, Warsaw was among the European capitals to confront the global financial crisis of the last decade with a degree of success.

Despite all this, the slogan deployed by Kaczynski for his 2015 election campaign was “Polska w ruinie” “Poland in ruins”. While remaining formally outside of the government (he is “merely” PiS’ party leader), Kaczynski is Poland’s undisputed de facto leader. His argument has been that while the post-1989 transition did indeed create wealth, it also left too many “defeated” citizens behind.

No effective social security cushion was introduced to take care of those who have not been able to ride the wave of economic success—so Kaczynski’s narrative goes—and temporary labour contracts have been too-widely used (25% of workers have fixed-term contracts, one of the highest percentages in Europe). Furthermore, according to this view, pure individualism was rewarded to the detriment of social cohesion. In the 2015 campaign, he promised a great deal of welfare in his election campaign, and his message made an impression on both those defeated by the transition period and those who, in spite of having achieved a degree of economic security, felt that the time had come for greater social protection.

As explained in a recent analysis published by the Brookings Institution entitled Why are Poles unimpressed with Poland’s economic achievements?, there is no contradiction between the higher level of wellbeing enjoyed by the average Pole today and the need for more substantial welfare. “Poland’s rapid economic ascent created new challenges […]Workers moved from farms to factories and then to offices, with a significant increase in temporary or “junk” contracts and relatively limited social assistance. Together with automation trends, and its adverse impact on low-skilled jobs, many working-class families faced heightened anxiety and uncertainty about their future”, notes the paper.

The PiS government—initially presided over by Beata Szydlo, who was replaced at the end of 2017 by Mateusz Morawiecki—has approved important welfare policies. The most important of these have been family allowances, with 120 euros a month for every child if there are at least two children in a family. This allowance is paid until the age of eighteen, regardless of the parents’ income. This is a large sum of money considering that the average wage in Poland is 1,100 euros before tax.

The government has introduced other social measures in addition to the family allowance. There are plans for council houses, for example, and incentives for students and the elderly. Pensions have also been increased and the retirement age, raised to 67 by liberal governments, has been lowered to 65 for men and 60 for women.

The massive growth in state spending initially prompted fears that the deficit ceiling would be breached, but robust growth in recent years—2.9% in 2016, 4.5% in 2017 and possibly 5% or more this year—has allowed the government to keep its accounts in order.

The government has played a leading role not only in implementing far-reaching welfare policies, but has also moved to reacquire strategic assets on behalf of the state, especially in the banking sector. Behind all this likes a specific strategy—to rebalance the ratio between foreign and local capital. According to Kaczynski, during the transition, the extremely advantageous conditions made available to foreigners penalised local capital. Within this framework, the government has introduced new criteria for foreign investment which—even more than EU funds—remain the main driving force for Poland’s growth.

The objective is to implement a policy of selective investment, favouring those that offer greater innovation. This means a significant shift in Poland’s model for attracting foreign capital to one based as much on quality than quantity. In the past, the primary interest of many investors has been to bet on Poland because of low manufacturing costs, although this is not the only factor that has made the country competitive.

In many ways, Kaczynski’s economic policy is similar to Orbán’s in Hungary. It is a mix of welfare and statism, while remaining open to foreign investment. The process involving the state’s “grasp”—part of a sort of “social pact” based on the concession of targeted economic benefits in exchange for tolerating a degree of authoritarianism—is another similarity. In Poland as in Hungary, the government has transformed state-owned radio and television into a propaganda machine and progressively assumed control over the judiciary, taking control of the Constitutional Court and the National Judiciary Council, which is the magistrates’ self-governing body.

The same operation was not successful with the Supreme Court, the country’s most important judicial body. Last year, the government had parliament vote on a law that would have ensured the early retirement of elderly judges so as to replace them with magistrates close to PiS leaders. The European Commission, however, successfully petitioned the government to take a step back, having previously failed in a similar injunction when PiS stacked the Constitutional Court and the National Judiciary Council.

Warsaw’s reconsideration had an electoral motive. Local elections were held in October, the first test since the 2015 general election. Law and Justice confirmed its position as the country’s leading party, taking 33% of the votes, a fair showing compared to the outcome of the 2015 elections (37.58%). It remained thus well ahead of the liberal Civic Coalition (26.7%). PiS won in various regions but suffered defeat in the battle for the cities. Generally speaking, this conflicting result was a return to the regional cleavage but also a very clear signal. While welfare and sustained growth have helped the government retain a fragile consensus in recent years, moderate urban voters nevertheless expressed intolerance for authoritarianism and returned a clear vote for the liberals.

There is now the need to avoid a head-on collision with Europe. This will require, in view of the European elections in May and the general election that will be held this October, a less antagonistic posture toward Brussels, Berlin and the entire European liberal world than in past years. The risk of seeing Brussels embark on violation procedures due to a deficit of democracy, in addition to the possibility of a contraction in the flow of EU funds hinted at by Warsaw’s main trade partner, Berlin, is encouraging Poland to cosmetically moderate its erstwhile recalcitrant attitude.

Translation from Italian: Francesca Simmons

Photo: JANEK SKARZYNSKI / AFP

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).