Jiang Zemin’s death (17 August 1926 – 30 November 2022) coincided with a wave of protests against the current Chinese government’s zero-COVID policy. He came to power in China as the result of waves of protest in favour of political reform in 1989. China has changed in many fundamental ways over the last three decades and Jiang was an important leader during that change. In contrast to the current situation, his period in power may be perceived to have been more open. This may imbue the celebration of his memory with a nostalgia for some “good old days”, implying criticism of a more negative present. Criticism of those in power by paying homage to figures from the past is a longstanding Chinese tradition.

Jiang’s powerbase was Shanghai. He became the mayor there in 1985, having trained to be an engineer and with experience in trade missions. In 1987 he became General Secretary of the Shanghai branch of the Communist Party of China (CPC), a more powerful position, and was promoted to the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPC. Deng Xiaoping was the “Paramount” leader at the time. The only high-ranking position Deng held was that of Chairman of the Central Military Commission (“political power grows out of the barrel of a gun”, Mao Zedong had written). Deng chose Hu Yaobang to be General Secretary of the CPC and Zhao Ziyang to be President of the State Council, but Deng was the unquestioned “core” leader of the CPC and the country, together with the Central Advisory Committee (CAC) of revolutionary veterans who had put an end to the Maoist period and tutored the reform period, of which he was Chairman.

The “opening up and reform” policy Deng promoted had its origins in the economic policy of Chen Yun in the early 1950s, a policy interrupted for two decades by radical Maoism, and revived when Deng consolidated his hold on power in 1978. “Opening up” meant ending autarky and allowing foreign direct investment (FDI). “Reform” was limited to the controlled introduction of incentives and market forces to generate wealth. Reform was accompanied by greater tolerance of intellectual and artistic freedom. This was a temporary policy designed to discredit the remaining radical Maoists in the CPC and to win wider support for Deng’s policies. Political reform was not contemplated. By the late 1980s various sectors of Chinese society wanted reform to be wider and to move faster and this led to public demonstrations. Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang were relatively sympathetic to these demands, but they frightened the Party elders of the CAC.

When the demonstrations increased in 1989, Jiang Zemin kept them under control in Shanghai, but they grew more multitudinous in Beijing, and this led to the downfall of Hu and Zhao. Hu died shortly thereafter, and the commemoration of his memory became a challenge to the regime. He was perceived to have been more open and tolerant, so praising him was understood to be a criticism of those who removed him from office. The military intervention in Beijing ended the demonstrations. Because of his management of events in Shanghai, Jiang was given the role of General Secretary, making him the third generation of CPC leadership (Mao and Deng were the first and second generations, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping are the fourth and fifth generations).

The position does not always give power. Mao had chosen Hu Yaobang to be his successor, but Deng was able to outmanoeuvre him. Jiang was General Secretary, but Deng and the CPC elders kept control. The events of 1989 divided the elders. Chen Yun and Li Xinnian were suspicious of the pace of reform. Yang Shangkun and Peng Zhen supported Deng. Jiang Zemin wanted to keep a tight control over the reforms, in accordance with the “hard left” elders, but even though he had given up all of his official positions in 1989, Deng short-circuited his critics and Jiang by making a tour of southern China in 1992 and proclaiming that it was “glorious” to “get rich”. Thereafter the CAC was disbanded, and reforms were accelerated. Jiang then successfully managed the reform process that transformed China’s economy, together with Zhu Rongji, an ally from Shanghai and an expert in economics. Key to this process was China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation, negotiated by Zhu. This integrated China into a rules-based international market system. It also gave China the opportunity to try to reform international organisations from within. Voting systems in key international organisation were weighted in favour of North America and Europe, to the detriment of “the global South”. As a result, China’s participation would shift part of the power away from the G7 to the G20, and China could try from within to reform trading practices that were prejudicial to its interests.

Opening China’s economy to a possible dependence on international markets, international rules and foreign investment was seen to be a great risk by leftists and traditional Maoists in the CPC. Jiang’s ideological justification of market liberalisation and the privatisation of state-owned enterprises was the doctrine of the “Three Represents”, that the CPC should represent China’s advanced productive forces, China’s advanced culture, and the fundamental interests of most of the Chinese people. In practice this meant the integration of intellectuals, scientists, engineers, cultural workers, economic managers and private entrepreneurs into the CPC, the worker’s party, thereby redefining the meaning of “the working class”. In 2002 the “Party of Collective Ownership” (the literal translation of the name of the CPC in Chinese) amended its Constitution in order to accept private entrepreneurs (“Red Capitalists”) into its ranks and to recognise certain forms of private ownership. Jiang managed to have his “Three Represents” doctrine enshrined in the Constitution, but not his name (Mao, Deng and Xi have had their names included in the Constitution, but not Jiang or Hu).

Despite the nostalgia for a period perceived retrospectively to have been more open and tolerant under Jiang, he did not advocate or allow political reform and was noted for his government’s repressive policy toward the Falungong movement. China’s rapid economic growth was not equally beneficial for all sectors of society. Prices rose. People working in the private sector could increase their salaries, but people on fixed incomes could not. This tended to affect middle-aged people, many of them members of the CPC. The Falungong movement adapted traditional Chinese physical activities such as Qi Gong, practiced by many of the people on fixed incomes. The government considered Falungong to be a dangerous sect and moved to prohibit it (on grounds like those used by European governments to control Jehovah’s Witnesses, Baha’is and similar groups). Since it was difficult to distinguish between the traditional practice of Qi Gong and the new variant of Falungong, non-members of the movement were also repressed. At the same time, the practice of Qi Gong could be interpreted to be a form of protest against government policy, an expression of social discontent and unrest among a key sector of the professional population, difficult to repress because it was a traditional activity. The Party-State in China is suspicious and intolerant of any movement or tendency it cannot control, especially when such a movement emerges from within Chinese culture, not because of foreign influence or interference. So, Jiang repressed the movement.

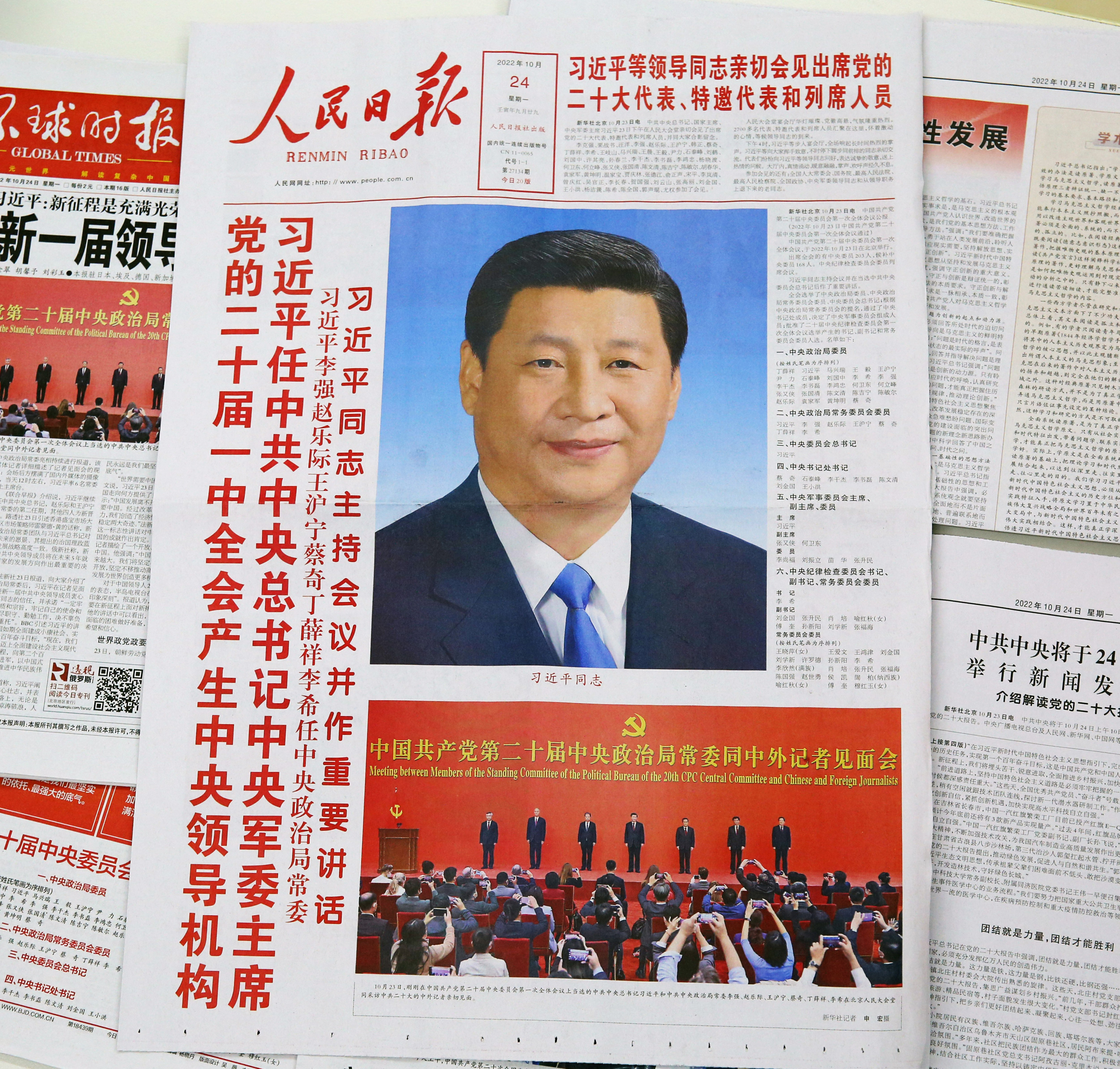

The radical Maoist period had been traumatic for the country and for the CPC. An attempt was made to avoid one man rule in the future by promoting intraparty democracy or collective leadership. There are three pillars of power in China: the CPC, the State Council, and the Central Military Commission (CMC). In theory they are separate but equal. The Party and the State each have their own constitution and their own authority, but in practice, the CPC is more equal (the CMC reports to the Party, not to the State). It is often difficult to distinguish which pillar of power is more decisive when the same person presides over all three of them (as does Xi Jinping currently). Deng and the elders wanted different leaders to preside over each branch (while maintaining their own decisive influence). The deaths of the elders removed their influence. Deng died in 1997, but he managed to prevent Jiang from choosing his successor, placing Hu Jintao in place to succeed Jiang in 2002. Jiang ceded control of the CPC and the State Council to Hu in 2002 but clung to his position as Chairman of the CMC in order not to lose influence. He was criticised for this and stepped down in 2004 but managed to prevent Hu from choosing his successor by manoeuvring Xi Jinping into position to take over in 2012 (Xi then proceeded to distance himself from both Jiang and Hu and has avoided having any successor, yet).

Jiang’s influence over the Hu and Xi administrations waned, but he did try to maintain some control through “the Shanghai clique” of officials he had named while in power. In later years he became a popular and generally good-humoured “meme” because younger Chinese netizens likened him to a toad for his appearance. They liken Xi to Winnie the Pooh for the same reason. It will be interesting to see how these two memes will play out now on the Internet.

LOVE this new paper from @fangkc on the Jiang Zemin toad meme

“Collective exploration and discovery of counter-discourse from right within the system”https://t.co/vIECEFCjNi pic.twitter.com/uFv73Q7XDB

— Peter Martin (@PeterMartin_PCM) June 22, 2018

Seán Golden is Associate Senior Researcher at the CIDOB Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (www.cidob.org).

Cover Photo: A huge portrait of Jiang Zemin is displayed in front of the Forbidden City in occasion of the 70th founding anniversary of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing, Oct. 1, 2019. (Xinhua/Pan Siwei via AFP).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.