The winds of change have arrived in Poland. After eight years of sovereignist and populist-driven government, the conservatives of the Law and Justice (PiS) party must stand down. As a result of last Sunday’s parliamentary elections Jaroslaw Kaczyński’s party remains the leading party but the election awarded the parliamentary majority to the democratic left: the liberals of Civic Coalition, the centrists of Third Way, and the leftists of Lewica. Together the three parties achieved almost 54 percent of the vote allowing them to gain an overwhelming majority in the Senate, winning two-thirds of the seats (66) against PiS’s 34.

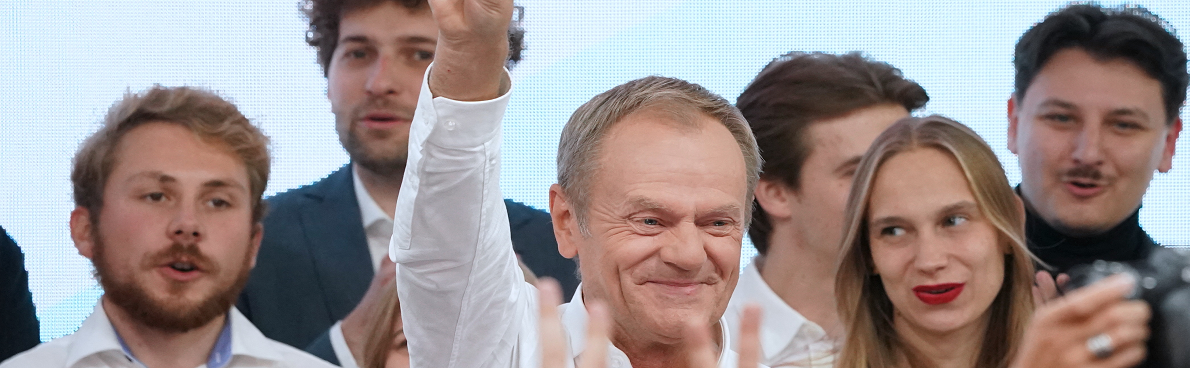

This shift leftwards not entirely unexpected. In recent months two massive demonstrations organized by Civic Coalition leader Donald Tusk had punctuated the run up to the elections. The first, on June 4, gathered 500,000 people. The second on October saw nearly 1 million participants. A clear sign that a good part of the country was ready to turn a new leaf.

Law and Justice got 35.4 percent of the vote, more than a third of the total, but it was not enough. In recent years the party has played the polarization card while creating a very loyal voter base, however the inverse effect was pushing away dialogue with other political parties for a possible coalition government. Even the ultra-right wing Konfederacja, which still fell far short of expectations, with only 7.1 percent of the vote, said it did not want to enter into talks with PiS.

What the PiS leadership did not expect was the mass participation in the vote against them. 74.4 percent of eligible voters went to the polls, the highest turnout in an election since Poland became democratic. Above all, young people went to vote, in some cases standing in line for hours in front of the polling stations. They ended up being the real key to this election.

In the 18-29 age group, the turnout was 68.8 percent. Four years ago it had been 46.4 percent. Young voters first and foremost rewarded Civic Coalition, Donald Tusk’s party, with 28.3 percent of the vote. This was followed by Lewica’s Left with 17.7 percent. At 16.9 percent were the centrists of the Third Way and the far-right Konfederacja (the latter a figure not to be underestimated). Right and Justice received only14.9 percent.

The abortion spark

The phenomenon can be explained by the major mistake Law and Justice made three years ago. After the 2019 parliamentary elections, the party was sailing firmly above 40 percent in the approval ratings. Everything changed on October 22, 2020, when the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, one of the first institutional bodies to lose its independence four years earlier, issued a ruling that went on to amend the abortion law, restricting access to it almost completely. A ruling with a political flavor, the instigator of which was clearly Law and Justice. Already twice in previous years pro-life associations close to the government had tried to bring bills to parliament to tighten the conditions of access to abortion. In both cases they had had to back down due to popular protests. It was during the 2016 czarny protest (black protest) that Straik kobiet (Women’s Strike), the feminist collective that would coordinate the demonstrations four years later, was born.

For months after the ruling, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in protest. The pact of trust between government and citizens had been broken. In just a few days, Law and Justice lost about 10 percent in the polls, which was never fully able to recover. Above all, a momentum of participation was created among young people (and especially young women), those most affected by the change in the law.

The role of the Constitutional Tribunal, now drained of its independence, also suddenly made clear the danger of the reforms implemented by the government in previous years and which had already alarmed the European Commission.

The European question and other challenges

The clash between Warsaw and Brussels is the second factor to be considered in reading the outcome of this election. This was not an election like any other; it was a crossroads. Voters could choose between “Orbanism”, conservative and illiberal, which would have led the country to cut ties with the European Union even further. And, on the other hand, a pro-EU coalition led by Donald Tusk, who had previously been president of the European Council for years. The choice was clear: with Brussels or against Brussels.

The Poles chose the first path, and now reconciliation can begin after years of struggle.

The job that will fall to the new government, however, will not be easy. The first challenge will be precisely restoring the rule of law. Reforming the judiciary so that a clear separation from the executive power is recreated, is essential to access the 35.4 billion euros from the Recovery fund that the EU Commission is holding back, but also to create the conditions for the unfreezing of cohesion funds, linked precisely to respect for the rule of law.

Poland urgently needs this money for necessary investments in energy transformation, digital and infrastructure development. The main obstacle will be the President of the Republic, Andrzej Duda, who has veto power and comes from Law and Justice. The number of seats won (248), despite representing a solid majority is far from the number needed to bypass the president’s veto (276).

In this sense, the new government must expect a number of obstructionist operations, both from the highest office in the state and from the new opposition. Next year there will be European and local elections. Kaczyński aims to quickly reorganize the ranks of the party for a quick redemption at the ballot box and thus arrive with momentum to the 2025 presidential elections. Should the Civic Coalition and its allies fail to get a less unbalanced president elected, the victory of recent days could be blunted.

Heading off these possible pitfalls, however, will require a strong and cohesive majority. The greatest risk for the future is that the different elements that make up the front that has united against Law and Justice will disunite. The distance separating, for example, Lewica’s left from the Third Way centrists is great, especially on such fundamental issues as abortion rights. It will be up to Tusk’s political skill to work to mediate between the parties.

Returning populists

For one populist that exits, there is another that enters. The Polish elections were preceded two weeks ago by the Slovak vote. The winner was former premier Robert Fico, of Smer – SD (Direction – Social Democracy), who with 22.9 percent of the vote edged out the pro-Europeans of Progressive Slovakia (17.6 percent), in an extremely fragmented political landscape. Fico has been a Social Democrat in name only for years now, and after resigning as prime minister in 2018 he veered toward a populism with rather heated overtones. During the pandemic he embraced the antivaxx cause, while at the outbreak of the war in Ukraine he openly positioned himself on Moscow’s side. Precisely because of this radicalization it was not a given that he would succeed in forming a government. Instead, within a couple of weeks he managed to reach an agreement with Hlas – SD (Voice – Social Democracy), the party of former prime minister Peter Pellegrini, which was born precisely from a split in the Directorate, and with the nationalists of the Slovak National Party (SNS).

According to the agreement reached we can expect Slovakia to take the “Hungarian” path: foreign policy based on NATO membership and European membership, but questioning the military aid to Ukraine, as Fico had already announced during his election campaign. Fico’s words on migration were also worrying: “We will use force to protect our country from migrants and measures will be taken immediately to resume border controls with Hungary.” In recent months there has been a marked increase in the flow of people from the Balkan route from the Magyar border.

The small central European country is thus poised to replace Poland in Brussels’ concerns. However, Fico will also have to look carefully at domestic political dynamics. His majority will not be solid: 79 seats out of 150 do not guarantee the stability and security that every populism feeds on.

Cover Photo: Poland’s main opposition leader, former premier and head of the centrist Civic Coalition bloc, Donald Tusk addresses supporters at the party’s headquarters in Warsaw, Poland on October 15, 2023, after the presentation of the first exit poll results of the country’s parliamentary elections. (Photo by Janek Skarzynski / AFP)