When English settlers came to the “new Zion,” they behaved much like Israeli Zionists today. What’s the lesson? This is the first part of an article originally published on Salon, on March 31st 2024. The second part can be found here.

“Humankind cannot bear very much reality,” T.S. Eliot wrote in the first of his Four Quartets. Today’s Israel-Hamas war and America’s own increasingly warlike divisions are forcing some of us to bear realities we haven’t borne quite so heavily before. Some of those realities involve attitudes against Jews that Eliot held and that may have become menacing again — as have the recent frantic efforts to censure antisemitism itself, sometimes in ways that risk prompting even worse antisemitism.

But larger eruptions of hatred and mayhem in America’s increasingly divided, uncivil society are driven not by antisemitism or by today’s Jews, nor by the riptides of global capital and technology and the desperate migrations and belligerent nationalisms that they accelerate. More than most of us recognize, they’re driven by ancient religious passions that figured deeply in Israel’s and America’s origins. Both nations’ professedly “liberal” and civic-republican cultures are profoundly and perhaps fatally conflicted, in ways that prompt not only news headlines but also biblically resonant upheavals, even when the participants don’t consider themselves religious at all.

Some of these conflicts have generated the Trump phenomenon, but Donald Trump and his media heralds, political acolytes and allies — including most evangelical Christians and many Orthodox Jews — aren’t the progenitors of these conflicts; they’re carriers of a deeper plague. Similarly, the belligerent Jewish nationalists who currently govern the State of Israel are accelerants of a doom-eager Zionism that isn’t new in history and that some of the Bible’s own prophets condemned.

Few of us can bear very much of such realities, whether in America or in Israel. I want to make a few observations about the origins of America’s obsession with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

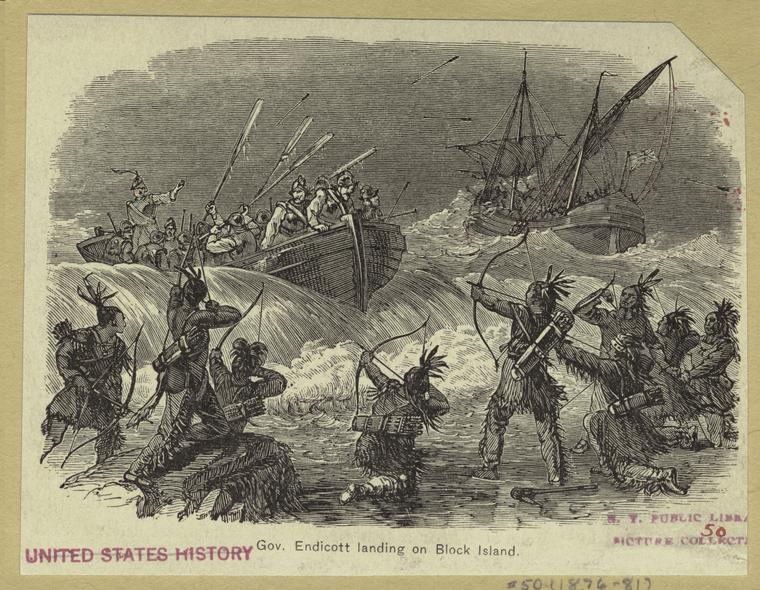

The 17th-century English Calvinists who colonized lands that they called New England and Virginia, and whose 18th-century legatees participated in founding the American republic, pursued strategies remarkably similar to those of today’s Israeli settlers in the West Bank and today’s military invaders of Gaza, some of whom claim a divine mandate and others a “manifest destiny” to impose one ethno-religious identity at the expense of longtime inhabitants.

In retrospect, American Puritans seem almost to have been “copying” today’s Israeli Zionists, tactic for tactic and pious justification for pious justification. Even more remarkably, Puritans justified what they were doing not by looking ahead 300 years but by looking back more than two millennia, emulating biblical Israelites’ “Hebrew republic” so intensely that they called themselves the “New Israel” and New England their “Zion.” They even put the Hebrew phrase Urim v’tumim, — meaning, approximately, “Light and Truth,” or “Light and Purity,” taken from the breastplate of the high priest in the Jerusalem temple — on the seal of Yale College, founded in 1701.

The “settler-colonial” paradigm (or accusation) touted by today’s American progressives in attacking Israel certainly fits the early American Puritans, who had no ancestral roots or claims on the lands they were settling and seizing. Yet their pivot backward toward ancient Israelites’ divinely promised “Zion” has infected America’s civic-republican culture in ways that still drive Protestants’ and Jews’ obsessions with Israel’s presence in the Middle East.

I experienced that strange convergence as late as the 1950s, growing up in Longmeadow, Massachusetts, an old Puritan town whose public school teachers still passed on echoes and remnants of its origins. I was also learning biblical Hebrew two afternoons a week in a nearby synagogue and, more intensively, in eight years of Jewish summer camp. When I entered Yale in 1965, in the twilight of its own Puritan ethos, I could read the Hebrew-lettered motto on its seal, and I knew that Yale’s president during my years there, Kingman Brewster Jr., himself born in Longmeadow, was a direct descendant of Elder William Brewster, the minister on the Mayflower in 1620.

In June 1967, you could have found me standing in line outside the Jewish Agency in Manhattan, hoping to register as a noncombatant in the Six-Day War. Not yet 21, I needed parental permission, which I didn’t get, so I didn’t go. But two years later, I was in Haifa and the Galilee with a small movement for Arab-Jewish cooperation, holding intense conversations with Palestinian citizens of Israel, as I’ve recounted in The New Jews, an anthology of essays by young American-Jewish activists of that time that I co-edited with the late scholar of Hebrew literature Alan Mintz. My own story only matters here because it showed me some origins of today’s controversy that are overlooked or mishandled by American Christians and Jews who are reckless with historical narratives, mythical or scholarly.

Ever since Jews’ own origin story, in Genesis 12:1, announced that God had told Abraham to “Go from your country [Ur, in Mesopotamia, ed] and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you,” Jews have unsettled, stimulated and exasperated other peoples because they had unsettled and uprooted themselves ever since their own “Abrahamic,” pivotal, “axial” break in human consciousness and conventions, becoming a tribe that negates a lot of what’s usually tribal in pursuing something broader.

A lot of this has been “too much” reality for many people and peoples to bear — Jews as well as non-Jews. The word “Hebrew” —ivry — means “He passed over,” as in crossing borders that are metaphysical and cultural as well as geographical, to pursue universal knowledge and justice across time as well as space. Many Americans and Israelis consider such pursuits essential to the Enlightenment, not to religion. But Abraham’s grandson Jacob, demanding to know the terms of the mission, wrestled with an angel for a whole night until the angel released him at dawn without an answer and renamed him Yisrael, which means, “He contends with God.”

That’s a myth for all of us, believers or not. Ancient Hebrews’ uprooting from Ur and their contentions elsewhere figured centrally in America’s own beginnings as a “nation of immigrants,” a land of clean breaks and fresh starts, and they figure now in our preoccupations with the Gaza war: from the biblical Abraham to Abraham Lincoln and beyond, the Hebraic origins of the American republic still matter, even as the country is becoming more gnostic, agnostic or libertarian, and less Hebraic and covenantal.

So let me make a few more observations about the original Jewish “axial” break from other traditions, and then about how New England Puritans transported that break into what has become our fraught, disintegrating civic-republican culture.

Jewish sublimity and its discontents

In the Genesis myth, Abraham doesn’t only leave Ur; he smashes its idols and even prepares to sacrifice his own son Isaac at the command of a hidden but omnipotent Interlocutor. Equally puzzling, the command is rescinded at the last minute, even as Abraham is preparing to obey it by binding his trusting son and raising his hand to strike the fatal blow. The father’s grief and loneliness are broken by the angel Gabriel, bringing a ram to substitute for Isaac in the offering. But Abraham has other disputes with God (over God’s decision to obliterate the corrupt cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, for example, killing many innocents). And Yisrael contends with God ever after.

These biblical accounts of the human spirit’s estrangements from nature turn the latter’s enticements into signs of human futility: A central prayer in the liturgy of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, originated the claim that “man’s origin is dust, and his destiny is dust,” depicting every individual life “as a fragile potsherd, as the grass that withers, as the flower that fades, as the fleeting shadow, as the passing cloud, as the wind that blows, as the floating dust, and even as a dream that vanishes.”

Such a scourging faith projects the faithful into a vast unknown between humans and their unknowable, sometimes irascible God. Its baring of human self-awareness prompts yearnings like Jacob’s to know God’s will and to identify human pursuits with transformations of a world that isn’t wholly indifferent to their efforts, so long as they keep a covenant that limits and repurposes tribal reliance on blood and soil.

“The Jewish nation is the nation of time, in a sense which cannot be said of any other nation,” the German Protestant theologian Paul Tillich explained in 1938:

It represents the permanent struggle between time and space. … It has a tragic fate when considered as a nation of space like every other nation, but as the nation of time, because it is beyond the circle of life and death, it is beyond tragedy. The people of time … cannot avoid being persecuted, because by their very existence they break the claim of the gods of space, who express themselves in will to power, imperialism, injustice, demonic enthusiasm, and tragic self-destruction. The gods of space, who are strong in every human soul, in every race and nation, are afraid of the Lord of Time, history, and justice, are afraid of his prophets and followers.

Afraid, indeed: “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me,” wrote Blaise Pascal, a French contemporary of the Puritans. That Jews have negated much of what’s tribal yet haven’t disappeared as a “tribe” themselves, at least in many other people’s minds, has angered some followers of Judaism’s derivative religions, Christianity and Islam, which claim to have superseded the Jewish faith and to have relieved humankind of having to bear too much reality in this fallen world.

“How odd of God to choose the Jews,” quipped journalist William Norman Ewer a century ago, capturing the mix of antipathy and admiration they have provoked ever since Judaism prompted its “axial” break in Western consciousness. You don’t need to “believe in” that break, in the religious sense, to notice that Jews have stimulated and exasperated other peoples among whom they’ve sojourned.

Christianity and Islam also acknowledge the Hebraic separation of spirit from nature: “We are all, in all places, strangers and pilgrims, travelers and sojourners,” intoned Robert Cushman, a contemporary of the Elder William Brewster and an organizer of the Pilgrims’ voyage, in a sermon he delivered in 1622. Islam commemorates Abraham’s readiness to sacrifice Isaac in a holiday, the Feast of the Sacrifice, that honors Abraham’s obedience and celebrates Isaac’s release.

But in Judaism’s judgment, these derivative religions fudge the starkness and sublimity of the separation of spirit from nature: In Dark Riddle: Hegel, Nietzsche, and the Jews, Israeli philosopher Yirmiyahu Yovel writes that Christians have depicted God “as a suffering, agonizing man, but thereby… transformed a human need into a theological principle that ends with an illusion” and “a false consolation.” For two millennia, Christians have intoned, “My kingdom is not of this world” and “Baptized in Christ, there is no Jew or Greek,” while sitting on golden thrones over armed states whose national identities are rooted even more deeply in ties of “blood and soil” than Jewish “tribal” identity has ever been.

Yet the Hebrew Bible shows that Hebrews were as terrified of existential uprootedness as Blaise Pascal or any Christian king. Even as Exodus recounts God revealing the terms of his covenant to Moses on the summit of Mount Sinai, the chosen people are busy fabricating and worshiping a Golden Calf at the foot of the mountain. Later they turn to kingly and materialistic protections against their wandering. Zionism appears in several historical periods as an attempt to return to and possess the promised land, the latest attempt provoked partly by an urgent need to escape rising persecution and even extinction.

But returning does not guarantee succeeding. For three millennia, Jews have invoked a “return” to Jerusalem from exile and a deliverance from “the Lord of time, history and justice” poetically and ritually, but not always really. Yet Jews have indeed returned at times to tribal or national service to “gods of space, who express themselves in will to power, imperialism, injustice, demonic enthusiasm, and tragic self-destruction.”

The Bible itself recognizes such ambivalence. In the Book of Samuel, Israelites importune its eponymous judge to “Give us a king to rule over us, like all the other nations.” Although that demand displeases not only Samuel but God, Samuel and the Israelites commit genocidal assaults against neighboring Canaanites, Amalekites and Philistines:

Remember what the Amalekites did to you… [when] they met you on your journey and attacked all who were lagging behind; they had no fear of God. When the Lord your God gives you rest from all the enemies around you in the land he is giving you to possess as an inheritance, you shall blot out the name of Amalek from under heaven. [Deuteronomy 25]

Then Samuel said, ‘Bring me Agag king of the Amalekites.’ Agag came to him cheerfully, for he thought, “Surely the bitterness of death is past.” But Samuel declared: ‘As your sword has made women childless, so your mother will be childless among women.’ And Samuel hacked Agag to pieces before the Lord at Gilgal. [1 Samuel 15]

Eight centuries before Christ, and 28 centuries before the Netanyahu government waged war against Hamas in Gaza, the prophet Amos said, “For the three transgressions of Gaza, Yea, for four, I will not reverse [its punishment]: Because they carried away captive a whole captivity [of Israelites] to deliver them up to Edom. So I will send a fire on the wall of Gaza, and it shall devour the palaces thereof; … and the remnant of the Philistines shall perish, Saith the Lord.”

So the militarized nationalism of today’s Zionists can be understood as another such reversion, reinforced in 2018 by the Knesset’s “Basic Law” declaring that Israel is “the Nation-State of the Jewish People,” and greatly diminishing it as a liberal democracy.

Such contradictory, conflicted uprootings and re-rootings have given Jews their atypical mobility, marginality and occasional magnificence and malfeasance, breeding some tough, defiant spirits, not only in Moses and Jesus but also in Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer, inventor of the atomic bomb and self-avowed “destroyer of worlds.” The Jew as interloper, living marginally in homogeneous societies but flourishing and sometimes predominating in pluralistic and open ones — agile, entrepreneurial, walking on eggshells and thinking fast – has sometimes seemed most “at home” in media of exchange, whether of information, money, merchandise, music, math, medicine or scientific discovery. Confirmation of their prominence in those realms is presented sociologically and lyrically in anthropologist Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century.

That Jews, unlike Puritans, actually do have ancestors in their “promised land” was confirmed in 1947 by the discovery of scrolls transcribed in Hebrew and buried in caves near the Dead Sea seven centuries before Islam existed and before Arabic was spoken in the region. That complicates the “settler-colonial” paradigm, which applies readily to English Puritans but more ambiguously to Jews. Yet those passages also contain prophetic warnings that Israelites’ territorial claims were contingent on keeping the covenant sealed at Sinai — or, as we might put it now, on transcending narrow tribalism to meet a higher, more universal standard. If they didn’t, God would punish them at the hands of their enemies:

Woe to those who are at ease in Zion, and to those who feel secure on the mountain of Samaria, the notable men of the first of the nations, to whom the house of Israel comes! …. Go down to Gath of the Philistines. Are you better than these kingdoms? Or is their territory greater than your territory, O you who put far away the day of disaster and bring near the seat of violence? Woe to those who lie on beds of ivory and stretch themselves out on their couches, … who drink wine in bowls and anoint themselves with the finest oils, but are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph! [Amos 6]

The reluctant but overwhelmed prophet Isaiah reported that God would punish the Israelite elites’ arrogance by destroying their Zion “until the cities lie ruined and without inhabitant, until the houses are left deserted and the fields ruined and ravaged, until the Lord has sent everyone far away and the land is utterly forsaken.”

How America’s Puritans became the “new Israel”

Puritans tried to Hebraize their Christian quest for personal salvation in Christ by grounding it in covenanted communities of law and collective discipline. But they had to reconcile their attraction to the gods of space and power with the biblical prophetic condemnations of it. Those condemnations were useful enough when Puritans faced defeats at the hands of the enemies they called “Indians,” reminding them that God had sometimes used the Israelites’ enemies to punish the chosen people for their sins. Puritans’ days of “fasting and humiliation” were essentially rituals of atonement, meant to affirm the participants’ righteousness — in the Puritans’ case, their conviction that they had superseded Israel.

It’s remarkable how closely the early American Puritan strategies, including mass murder, anticipated those of today’s Zionist settlers on the West Bank and the IDF in Gaza. In 1637, Puritan soldiers surrounded a major settlement of Connecticut’s Pequot people as Puritan leader John Mason “snatched a torch from a wigwam and set fire to the village, which, owing to the strong wind blowing, was soon ablaze,” according to James Truslow Adams’ 1921 Pulitzer-winning “The Founding of New England”:

“In the early dawn of that May morning, as the New England men stood guard over the flames, five hundred men, women, and children were slowly burned alive.” Ministers of Christ saluted one another “in the Lord Jesus,” some of them profiting directly from selling surviving Pequot boys and girls into slavery.

A few decades later, in 1676, future Harvard president Increase Mather urged and then celebrated a genocide of the Narragansett people, declaring, in his chronicle of “The Warr with the Indians in New England”:

The Heathen People amongst whom we live, and whose Land the Lord God of our Fathers hath given to us for a rightfull Possession, have at sundry times been plotting mischievous devices against that part of the English Israel which is seated in these goings down of the Sun…. And we have reason to conclude that salvation is begun [because] there are two or 3,000 Indians who have been either killed, or taken, or submitted themselves to the English…. [T]he Narragansetts are in a manner ruined… who last year were the greatest body of Indians in New England, and the most formidable Enemy which hath appeared against us. But God hath consumed them by the word, & by Famine and by sickness.

Gregory Michna, a historian of that war, writes, “Just as [the biblical] Canaan was wrested from the hands of heathens through sacral violence… the Rev. Joshua Moodey advocated infanticide as a wartime strategy, writing that ‘The Bratts of Babylon may more easily be dasht against the Stones, if we take the Season for it, but if we let them grow up they will become more formidable, and hardly Conquerable.’”

Indigenous people made retaliatory attacks against the English, including an infamous 1704 example in Deerfield, Massachusetts, by the measures of its time nearly as horrifying as last October’s Hamas attack on Israel. The Deerfield attack has figured deeply in my own moral imagination ever since a February morning in 1957, when my fourth-grade class — some of them descendants of the original Puritan settlers — sat on the floor, with the lamps turned off for effect, as Miss Ethel Smith stood before us in the pale, wintry light and told us that on another cold February morning, 250 years earlier, howling, hatchet-wielding “Indians” had slaughtered nearly 20 English settlers of Deerfield, 40 miles upriver from us, and then force-marched nearly a hundred more through the frigid wilderness to captivity in Canada.

The captives included Deerfield minister John Williams and his family. Two of his children were killed in the attack and his wife, Eunice, became weak on the trek north and fell down a ravine, tumbling into a river that swept her away. Williams’ account of that personal and communal calamity, all the more harrowing for its self-sacrificing affirmations of faith amid crucifixion, was published as The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion soon after he and his son Stephen returned to Massachusetts in a hostage exchange. His account rivaled John Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress” as a parable and primer for the Puritans’ holy but dangerous errand into the “howling wilderness,” as the historian John Demos recounts in The Unredeemed Captive; A Family Story of Early America, highlighting Williams’ daughter’s refusal to leave her Native captors to rejoin the English world.

Williams’ son Stephen later became the minister of Longmeadow’s Congregational church, which stands 100 yards from the classroom where Ethel Smith told us about his captivity. The great Puritan theologian Jonathan Edwards visited him there in 1740, and a year later Stephen Williams rode the five miles south from Longmeadow to Enfield, Connecticut, to hear Edwards preach his (in)famous sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” and write an eyewitness account of its listeners’ writhing reactions.

My belief that this matters may be overdetermined by the fact that, 200-plus years later, I bicycled along Williams Street every weekday, passing the church where Edwards had visited Williams, on my way to and from Miss Smith’s classroom.

Miss Smith didn’t tell us that the English had included some rogues, swindlers and mountebanks who drove the expulsions and massacres of Pequots, Pocumptucs, Mohawks, Narragansetts, Wampanoags and Abenakis. Despite their proclaimed good intentions, the settlers’ land hunger generated duplicitous trade and land deals, alongside pious missions to convert indigenous people into “praying Indians.” James Truslow Adams explains that:

As the whites increased in numbers and comparative power, and as their first fears of the savages, and the desire to convert them, gave place to dislike, contempt, spiritual indifference, and self-confidence… it was no longer considered necessary to treat with the Indian as an equal…. [T]he lands of the [Indians] gradually came to be looked upon as reservations upon which their native owners were allowed to live until a convenient opportunity, or the growing needs of the settlers, might bring about a farther advance.

Today’s Israeli settlers on the West Bank might take note and take caution. So might American patriots who have forgotten these and other precedents for our present civic-republican crisis. Even the Rev. Stephen Williams, a redeemed captive who returned from the attack on Deerfield in 1704, wound up owning Black slaves as his house servants in Longmeadow, as recent Harvard graduate Michael Baick recounts in a fascinating senior essay.

How America’s founders invoked biblical Hebrews

In the latter half of the 17th century, Cotton Mather, the son of Increase Mather and a tribune and chronicler of the Massachusetts Bay Puritans, learned Hebrew and studied the Old Testament to confirm that New England “fulfills the type of Israel materially.” Mather wrote that his Puritans, like the Hebrews making the Exodus from Egypt, had fled “slavery,” in their case under the Church of England, to establish communities “for the exercise of the Protestant religion, according to the light of their consciences, in the desarts of America.”

In 1771, the young James Madison, then a future framer and president, stayed on for a year at the College of New Jersey (later known as Princeton), to study Hebrew and Puritan theology.

In 1776, Benjamin Franklin proposed that the great seal of the United States depict “Moses in the Dress of a High Priest standing on the Shore, and Extending his Hand Over the Sea, Thereby Causing the Same to Overwhelm Pharaoh.” (The Continental Congress chose instead the Masonic-inspired seal now on every dollar bill.)

In 1809, John Adams, a descendant of New England Puritans and by then a former president, wrote, “I will insist that the Hebrews have done more to civilize Men than any other Nation. If I were an Atheist and believed in blind eternal Fate, I should still believe that Fate had ordained the Jews to be the most essential Instrument for civilizing the Nations.” Adams employed that “instrument” to advance something like the Hebrews’ covenant, writing in the preamble to the Massachusetts constitution, “The body politic is … a social compact, by which the whole people covenants with each citizen, and each citizen with the whole people, that all shall be governed by certain laws for the common good.”

Note what that entails: a civic-republican society is secured not only by institutional and legal authority but also by “understandings” that cannot merely be legislated. Nor can a civic-republican social compact be rooted ultimately in ties of “blood and soil,” the infamous German shorthand for ethno-racial, quasi-familial bonds that sustain a sense of intimacy among people who share what historian Benedict Anderson called “imagined community.” Rather, a civic-republican society must be based on a covenant, a semi-spiritual agreement among autonomous individuals to hold one another to certain public virtues and norms that neither the liberal state nor “the free market” can nourish or defend. Something additional, or foundational, is required — a civil society that relies not just on the rule of law but on the kind of “social compact” described by Adams.

Covenants require extralegal agreements, or traditions of trust, even among their competing participants, as much as they require laws that are otherwise too easily undercut by their enforcers. Thanks to such extralegal traditions, citizens accused of having broken the covenant are assured of hearings before a group of their peers, where they are informed of the charges against them and enabled to rebut or disprove the charges, if they can. A truly covenanted society cannot punish someone who hasn’t been convicted in such a process. A civic-republican society relies on an overriding sense of trust, even amid substantive disagreements among citizens. Thomas Hooker, the 17th-century “father of Connecticut,” invoked the model of the biblical “Hebrew Republic” in Election Day sermons to the settlers of that church-state, whose separation of religion and public law would come later.

In 1869, the British critic Matthew Arnold observed that Protestant Americans had internalized Hebraism’s scourging demands for “conduct and obedience” and “strictness of conscience”:

To walk staunchly by the best light one has, to be strict and sincere with oneself, not to be of the number… who say and do not, to be in earnest – …. this discipline has been nowhere so effectively taught as in the school of Hebraism…. [T]he intense and convinced energy with which the Hebrew, both of the Old and of the New Testament, threw himself upon his ideal, and which inspired the incomparable definition of the great Christian virtue, Faith — the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen — this energy of faith in its ideal has belonged to Hebraism alone.

“From Maine to Florida and back again, all America Hebraizes,” Arnold wrote, and Hebraic intrepidity and prickly fidelity indeed characterized the training of many American leaders and followers at prep schools like Groton, whose founding rector, Endicott Peabody, was a Puritan descendant. His students included Franklin D. Roosevelt, who continued to correspond with Peabody even after becoming president.

In 1987, historian Shalom Goldman discovered that George W. Bush’s great-uncle five generations removed, the Rev. George Bush, was the first teacher of Hebrew at New York University in 1835 and the author of a book on Islam, “A Life of Mohammed,” which pronounced the prophet an imposter. In 1844, the Rev. Bush wrote “The Valley of the Vision, or The Dry Bones Revived,” interpreting the biblical Book of Ezekiel to prophesy the return of the Jews to Palestine.

I don’t know whether George W. Bush has read his ancestor’s exegesis, but Barack Obama cited Ezekiel in his 2008 speech on race, recalling that at his Trinity Church in Chicago (a branch of the Puritans’ Congregational Church), “Ezekiel’s field of dry bones” was one of the “stories — of survival, and freedom, and hope” — that “became our story, my story; the blood that had spilled was our blood, the tears our tears.”

Obama seemed to want to weave back into America’s civic-republican fabric some tough old threads of Abrahamic, covenantal faith. Now that we’re looking through gaping holes in that fabric, the republic’s fate seems more contingent than ever on its founders’ hope that it could rely on “strictness of conscience” and citizens’ inner beliefs as strongly as on their outward performances and interests.

Much from those origins still animated American civic culture during my childhood but has gone missing during the 70 years since Miss Smith’s pronouncements implanted in an impressionable nine-year-old some of the old Puritan (and Hebraic) discipline. Even John Adams’ civic-republican culture seems to have given way to personalistic strains in evangelical Christianity and in the republic’s Lockean heritage.

It would be wrong for today’s faltering, formerly “mainline” Congregationalists, Presbyterians and other Protestants to displace onto today’s Israel their own discomfort about soulless neoliberalism or reactionary tribalism. If we could reweave older, stronger threads into our civic-republican fabric, we might remember that claims on sacred soil and blood are contingent on upholding principles that can’t be defended, much less inculcated, by armies and wealth alone.

The second part can be found here.

Cover photo: Illustration of the departure of the pilgrim fathers, for America. Dated 1620 (Photo by Ann Ronan Picture Library / Photo12 via AFP.)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).