The fall of Kabul confirms both the failure of Euroamerican efforts to dominate the region and an inevitable and irreversible decline of Euroamerican hegemony over the twenty-first century world order. It also re-focuses attention on the importance of the Afro-Eurasian land mass as the centre of world affairs.

It is interesting to compare how Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin analyse the Taliban’s’ return to power. Biden said the US did not go into Afghanistan to nation-build: ‘it’s the right and the responsibility of the Afghan people alone to decide their future and how they want to run their country’. He added that it is not rational to deal with women’s rights around the world with military force: ‘The way to deal with that is not with a military invasion. The way to deal with that is putting economic, diplomatic, and international pressure on them to change their behaviour’. Putin states the obvious, that Taliban control of the territory is the political reality: ‘one must proceed from these realities, preventing the collapse of the Afghan state’. He goes further than Biden in recognising the error of applying ideologies derived from the Enlightenment: ‘It is necessary to stop the irresponsible policy of imposing someone else’s values from the outside, the desire to build democracy from outside according to other people’s patterns, without taking into account any historical, cultural or religious peculiarities. Completely ignoring the traditions by which other peoples live’.

The failures of the Western outlook

Both capitalism and communism are Enlightenment ideologies contingent on western European history and culture. Adam Smith and Karl Marx were Enlightenment thinkers. Both professed to have discovered scientific laws as the bases of society. Both participated in a world-vision derived from concepts posited on only one true faith and a unique universal reason, that happened to coincide with European interests. Without specifically admitting the USSR’s own failed attempt to impose a European version of socialism on the country, Putin does acknowledge the lesson learned: ‘We know Afghanistan well, we know how this country is organized and how counterproductive it is to try to impose unusual forms of government and social life on it. Any such social and political experiments have not yet been successful and only lead to the destruction of the state, the degradation of their political and social systems’.

While Euroamerican strategists of the invasion of Afghanistan and the war in Iraq say they turned to the study of Sunzi’s Art of War after failing in Vietnam, thinking it would give them the key to victory, they seem not to have understood that non-state enemies have so radically changed the very nature of war that it is no longer easy to understand what victory might mean. Perhaps they should have studied the Pancatantra, an ancient Sanskrit text on strategy, that circulated in Persian and Arabic versions, centuries before Marco Polo travelled through Eurasia. Or even better, the Muqaddimah, a universal cyclical theory of history elaborated by Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406). A universal linear vision of history as progress toward a constantly improving future, giving rise to the fatal ambition for infinite growth in a world of limited resources, is another product of the Enlightenment. Ibn Khaldun perceived a pattern of the rise and fall of regimes over a 120-year periods on the basis of asabiyya, a unifying creed or identity, and umran, a form of communitarianism. He contrasted the asabiyya and umran of badawa, non-sedentary desert lifestyles with those of hadara, sedentary urban culture. Hardy badawa desert tribes united by asabiyya and their own form of umran, accustomed to survival tactics, hunting and warfare, overrun hadara urban civilisations that are weak in asabiyya and umran, accustomed to the pursuit of comfort and wealth and succumbing to corruption, weakness and disunity. Over three generations, the victorious badawa tribe acquires the vices of hadara culture, and the cycle repeats. A better understanding of tribal cultures and the analyses of Ibn Khaldun might have prevented many Euroamerican errors in Afghanistan and have provided better explanations of the Taliban victory than do simplistic identifications of Islam, rather than tribalism and nationalism, as the agglutinating force that drives them.

Testing Beijing’s strategy

NATO’s withdrawal leaves Iran, Russia, Pakistan and China as the major powers most closely involved with the emerging Taliban regime. Iran and Pakistan have more cultural affinities with the region than Russia or China, but it will be especially interesting to see how China’s role develops. The Chinese empire did not reach Afghanistan. China developed an Asian world order, a Pax Sinica, based on the exchange of tribute received from its neighbours, reciprocated by Chinese gifts. They realised early on that buying peace was more economical and beneficial than financing war. China was a sedentary culture, its neighbours non-sedentary. Imperial China’s relations with its neighbours were based on culturalism, not nationalism. Chinese culture was taken to be superior. If non-Chinese peoples acquired Chinese culture, they ceased to be non-Chinese. The tributary state system was not simply the maintenance of trade relations in peaceful circumstances. It also had the mission of extending Chinese values. The policy of 懷柔遠人 huáiróu yuǎnrén meant both ‘cherishing’ and ‘pacifying’ the faraway non-sedentary peoples. Thus, pacification could be accomplished through 共享太平 之福 gòngxiǎng tàipíng zhī fú, through wealth based on shared peace. In this way, the Chinese empire could 以不治治之 yǐ bùzhì zhì zhī, it could govern without governing.

In contemporary terms, this policy takes the shape of the Belt and Road Initiative, which would also pass through Afghanistan. The Taliban may have expelled foreign troops after twenty years of fighting, but their earlier stint in government demonstrated that rebellion or revolution are one thing but administering and governing a country are something very different and require a very different set of skills and experts. Afghanistan has opium, which the Taliban suppressed in the past, though it provides income. It also has rare earths, a raw material crucial to China’s development. It stands in the way of China’s path to Europe and, through Pakistan, to the Indian Ocean. This is a case ripe for China’s ‘win-win’ diplomacy. In return for facilitating China’s infrastructure projects and discouraging secessionist movements in Xinjiang province, the Taliban could also help to suppress popular resistance to Chinese projects in Pakistan. In return, China can provide investment and expertise.

But the Belt and Road Initiative is not simply a trade strategy. Although this comparison is unlikely to be made in NATO or EU contexts, much like the European Union’s policy of ‘regime change without firing a shot’ by offering membership in return for reforms, a policy that converted three member states from fascism to liberal democracy and ten former Soviet satellites, the Chinese hard power economic initiative also has a soft power component. In its own way, China also promotes education, women’s rights and respect for the rules of international trade and is not likely to provide investment or expertise in uncertain or unstable circumstances. Dealing with the Chinese may seem on the surface to be ‘no strings attached’, but in the long run it may not be entirely so.

Re-crafting diplomacy

The Soviet Union tried to create a secular society that provided education and rights to all through their Enlightenment model of socialism. NATO tried to do the same by formalising the structures of Enlightenment liberal democracy. Both Enlightenment models foundered on the reality of tribal societies and structures that they failed to take into account or disdained (like the jirgas and the loya jirga). Cold War politics also intervened, each side encouraging mujahideen forms of resistance that eventually frustrated and expelled the other. Afghanistan today is not a monolithic Taliban entity. Daesh will contest Taliban rule, as will non-Pashtun tribes, and the Taliban themselves are not a monolithic homogeneous movement. Perhaps the moment has come to give China’s millennial approach an opportunity to engage with the Taliban in the establishment of a stable state, rather than continuing to ignore the realities on the ground by reigniting mujahideen resistance against the Taliban.

Effective communication with both the Taliban and China would require a multicultural rhetoric that honours both universal values and culture-specific values based on rules that acknowledge the differences in moral orders on both sides, then look for common ground. A multicultural rhetoric must be sensitive to the respective moral orders, with special emphasis on mutual recognition, parity of esteem, and mutual benefit. Attach equal importance to all forms of human rights, including civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights as well as collective rights and the right to development. Using the appropriate forums for engaging in open-minded and critical debate with advisers and officials and identifying the most effective target audience for value diplomacy, that may not correspond to forums typical in Euroamerica, may have a real and direct impact on opinion-forming and policymaking. It is strategically important to collaborate with academics and advisers because such cooperation facilitates the exchange of ideas and the construction of a common and consensual multicultural civic discourse.

Will Biden and Putin act in consequence of the conclusions they have drawn?

Seán Golden is Associate Senior Researcher at the CIDOB Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (www.cidob.org).

Bibliography

‘Full transcript of ABC News’ George Stephanopoulos’ interview with President Joe Biden’; https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/full-transcript-abc-news-george-stephanopoulos-interview-president/story?id=79535643

‘Russian President Putin says outside forces must not impose their views on Afghanistan’; https://edition.cnn.com/world/live-news/afghanistan-taliban-us-news-08-20-21/h_f42b5f7e364faa26c3ce7a6d03b3f69b

Devonshire-Ellis, Chris. ‘The Afghanistan-China Belt & Road Initiative’, Silk Road Briefing, 18/08/2021; https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2021/08/17/the-afghanistan-china-belt-road-initiative/

Golden, Sean. ‘New Paradigms for the New Silk Road’, in Carmen Mendes (ed.), China’s New Silk Road. An Emerging World Order, London: Routledge, 2018, 7-20

Kaplan, R.D. ‘The return of Marco Polo’s world and the U.S. military response ‘, CNAS – Center for a New American Security, 2017; http://stories.cnas.org/the-return-of-marco-polos-world-and-the-u-s-military-response

Khanna, P. ‘Connectivity and strategy: A response to Robert Kaplan’, CNAS -Center for a New American Security, 2017; http://stories.cnas.org/connectivity-and-strategy-a-response-to-robert-kaplan

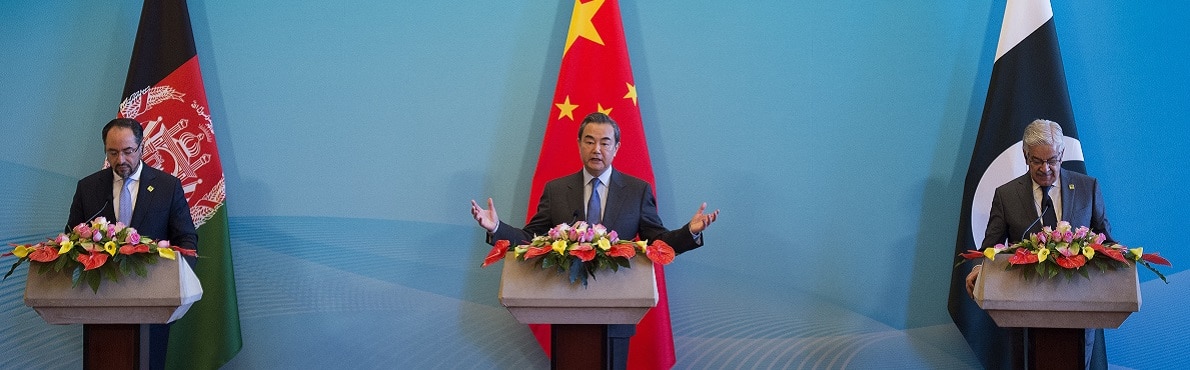

Cover Photo: China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi heading a joint press conference after the first China-Afghanistan-Pakistan Foreign Ministers’ Dialogue – Beijing, December 26, 2017 (Nicolas Asfouri / AFP).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.