The 10th of April marked the tenth anniversary of the tragedy at the Smolensk airport in Russia in which the President of Poland, Lech Kaczyński, his wife, and around 90 members of the country’s ruling class that were travelling with him, lost their lives. From Smolensk they were travelling to Katyn to mark the 70th anniversary of the massacre of twenty thousand Poles at the hands of Soviet forces in 1940, after having been taken prisoner the year before when Moscow and Nazi Germany had divided Poland.

While landing at Smolensk, the presidential plane hit a tree and crashed leaving no survivors. Two years ago, a memorial for the victims of the disaster was inaugurated in Piłsudski Square, in the heart of Warsaw. On the 10th anniversary, Jarosław Kaczyński, the late president’s twin brother, laid a wreath of flowers at the foot of the memorial.

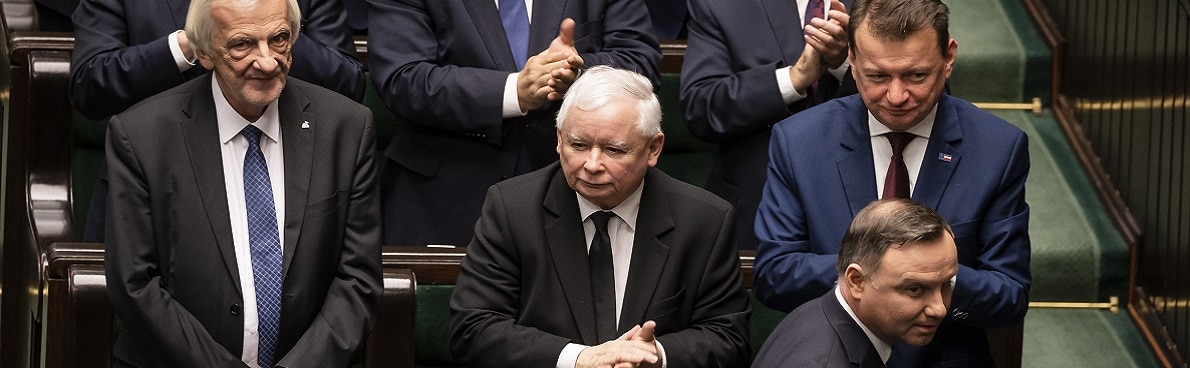

Jarosław Kaczyński is the leader of the Law and Justice Party (PiS), a populist party that has been in power since 2015, and many consider him the true leader of the country although currently he is only a member of parliament. Accompanying him on the anniversary were a number of PiS dignitaries none of whom were wearing masks or gloves nor were they respecting social distancing measures, as depicted in photographs taken at the event. Michał Szułdrzyński, deputy editor of the newspaper Rzeczpospolita, wrote that it was a bad example for citizens. In such a time as now, during a pandemic which requires that the population respect many prohibitions, including visiting the graves of loved ones, Jarosław Kaczyński seemed to be placing himself above the law even though his act was reasonable. Rule of law, Szułdrzyński claims, “works only if leaders set the example for their citizens, respecting the law”.

Rzeczpospolita is a conservative newspaper that overall seemed to welcome the PiS’s electoral victory in October 2015, though it has always maintained a critical attitude. This approach has intensified over time, shadowing the increase of the abuse of power by the majority. The last five years have laid the stage for a “taking over of the state” process analogous, in some respects, to what Viktor Orbán has implemented in Hungary. It is no coincidence that one of the 2015 electoral slogans of the PiS was “to bring Budapest to Warsaw”. The majority has occupied public companies, the state tv and radio as well as the organs of justice, going beyond the limits of a physiological spoils system.

Deteriorated rule of law

The judiciary has perhaps been subjected to the biggest changes. New laws have altered the composition and functioning of the Constitutional Court, the National Council of the Judiciary (a self-governing body with the task of overseeing the judiciary), and the Supreme Court, the only body vaguely resisting this assault. According to the European Commission, this has been a systematic gutting of the independence of the judicial branch. An infringement procedure has been opened and just a few days ago the European Court of Justice ruled that the Polish government retreat from one of the most controversial aspects of the judiciary reforms leading to a serious imbalance of powers.

Save for a few instances, the President of the Republic, Andrzej Duda seems to have indulged the line of the government, which although nominally led by Mateusz Morawiecki, many see as in fact “guided” by Mr. Kaczyński. The 48-year-old head of state, raided within the ranks of the PiS, is set up for election on the 10th of May and polls indicate that he is the favorite.

In a highly delicate phase, marked by an insidious virus that spreads easily (almost 7,000 infected and over 200 dead have been counted in Poland), holding an election is an enormous risk, yet the PiS does not intend to postpone it. The vote shall however be mailed in rather than in person. A law amending the electoral code for this purpose is currently shuttling between the Sejm and the Senate, the lower and upper houses of Parliament respectively.

The president is an important figure in the Polish political system because he can veto legislation. Overcoming it would require three fifths of the Sejm; a majority that the PiS does not have. Duda is currently the favorite, but if the election were to be postponed even by a few months, things could change. If the blow to the economy dealt by the Coronarvirus is harder than expected, undermining the generous welfare system put in place by the PiS over the last few years, which helped foster a large consensus, the opposition candidates could have a chance. With a president that is unrelated to the ruling party, such as the moderate Małgorzata Kidawa-Błońska, the PiS’s illiberal agenda may lose its momentum, and the presidential veto would not be circumvented. These are the scenarios, more or less likely, that seem to worry Kascynski, a man who many describe as living for the sake of power.

There is still no law on the mail-in election, yet the postal service is planning for the vote under a new director, the former minister of defence Tomasz Zdzikot, a leading member of the PiS. The former postmaster general, Przemysław Sypniewski, skeptical about the idea of organizing elections in so short a time, stepped down. Questions regarding this new voting format were also brought up by the Central Electoral Commission. In addition, some jurists believe that amending the electoral code just a month away from the elections is unconstitutional, while the liberal and left-wing opposition parties denounce the absurdity of an election supposed to take place without a classic electoral campaign.

The alternative to a mail-in ballot could be a constitutional amendment to extend the presidential mandate from five to seven years. The PiS has also added discussions on this measure to the parliamentary agenda, but a lack of time and he need to build a consensus (a constitutional amendment would require opposition votes) make this prospect unlikely.

Follow the money

In the meanwhile, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki has developed a weighty aid package that is worth around 15% of GDP, and the Central Bank has cut interest rates in order to give oxygen to the economy. The rising fear is that the inflow of European structural funds, a vital lever for the Polish economy, may decline. In Brussels there is in fact talk of reshaping the 2021-2027 budget to aid the countries most affected by the pandemic. Poland is the primary beneficiary of EU funds (it received 90 billion euros between 2014 and 2020) and will fight to maintain an important slice, as these funds are the only form of financial assistance they can count on from the EU. Not being a member of the Eurozone, Poland cannot count on any European Central Bank “bazooka”, Eurobond or the like.

It will be difficult for the country to maintain its funding quota, all the more as it is possible that the EU may also move to consider the quality of democracy in the allocation criteria. Central Europe, already under observation, has once more made headlines in recent weeks. In Hungary, Orbán obtained from Parliament full powers, whose effect is still to be assessed. Now in Poland comes the unbridled race towards a presidential vote that appears to be fairly plainly motivated by “power for the sake of power.” Added to this is the recent ruling by the European Court of Justice.

How will Europe’s larger players react to all that? Will they punish Warsaw (and Budapest)? That remains unclear: the “if” as much as the “when”. Budget negotiations will not take place, as it seems, before autumn. Kaczyński could force the mail-in vote and lock down Duda but lose funds. Or he could stop everything and postpone the vote to get a better chance at the European level; but in this scenario, he would lose credibility amongst his base and perhaps bet on the wrong battle. The Polish economy could collapse anyway, or perhaps recover with its own resources. The game is full of unknowns.

Photo: Wojtek RADWANSKI / AFP

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).