“I think the Right is starting to realize that one of their biggest mistakes ever was letting go of nature, in so many ways. National identity is your heritage, and I don’t understand why this topic is now dominated by the leftists, who soil such a pure topic, that is environmental protection, by enmeshing it with gender ideology and bullshit of the kind.”

The author of this quote is in many ways emblematic of the misconceptions one often has about the (radical) right. Elek is an educated young man, who is finishing up his PhD and simultaneously works at an organic farm in the north of Hungary. This does not make his views less abominable, for Elek has more than a decade of experience in the 64-Counties-Movement (HVIM), a far-right movement advocating for the return to The Greater Hungary (pre-Trianon) borders, which has led Elek to quite a few troubles with the law. Even for the Hungarian far-right landscape, spanning from radical-right parties such as Jobbik and Our Homeland (Mi Hazánk), to more extreme movements such as The Outlaw Army (Betyársereg) and Hungarian Self-Defense Movement (Magyar Önvédelmi Mozgalom), HVIM is often considered to be an extreme-right movement. A characteristic of the Hungarian far right ever since mid-2000s is the dominance of one main party (then Jobbik and now Our Homeland) which coordinates the loose network of various radical and extreme-right movements (such as The Outlaw Army and HVIM, among others).

The reason why I talked to Elek, apart from his membership in one of the most renowned far-right organizations in the country, is his environmental activism. Elek is an informal leader of the HVIM’s “green” section, and the administrator and the chief editor of the Facebook page, Zöld Ellenállás, which now has close to 3,000 followers. The group has its own hashtag, #greenisnotleft, which adequately encapsulates the motivation of its founder. In fact, the group was founded in late 2018, admittedly after Elek was inspired by the interview I conducted with him. Amid its (relatively small) outreach, the group offers an outlook on how ideology can influence the framing of environmental issues.

The principal aim of Zöld Ellenállás (ZE) is in establishing a sharp distinction from what is perceived as the ‘globalist’ and ‘mainstream’ environmentalism. By placing an emphasis on the ‘rooted’ nature of species, hence human beings, ZE promotes naturalist logic of “situatedness” – in showing how everything has its place, Elek envisages nature as a blueprint for the social order. Following this logic, nations are containers where authentic species live in an equilibrium, thus forming an authentic ecosystem. At the same time, naturalist logic also goes against anything supposedly challenging the established creed of ‘natural’ or ‘normal’, for instance espousing anti-immigration or anti-LGBTIQ+ attitudes. To prove the point, the content of ZE points to ‘racoons’ and ‘migrant bugs’ found in Hungary which are harmful to the ecosystem rooted in the Carpathian Basin, the natural container of the Hungarian nationhood. The content of their claims is certainly justified (such as the post about the loose pet: South American coati – Ormányos medve, which was noticed wandering around in the hills of Buda), but a great number of posts are framed to reach xenophobic or blatantly racist conclusions. Potential examples include the contribution of “Gypsy settlements” to illegal logging in Slovakian Tatras, or the post on an Indian poacher who allegedly killed and later ate a tiger’s penis because of its supposed aphrodisiac powers (with a picture of the allegedly convicted man from India). Logically, the comments to this post gathered a number of members of Mi Hazánk, Hungarian far-right party, explaining the backwardness of Indians and the broader argument on the ineptness of non-Christian migrants to reside in the European (or in the words of Mi Hazank’s leader Laszlo Toroczkai, “Northern”) civilization.

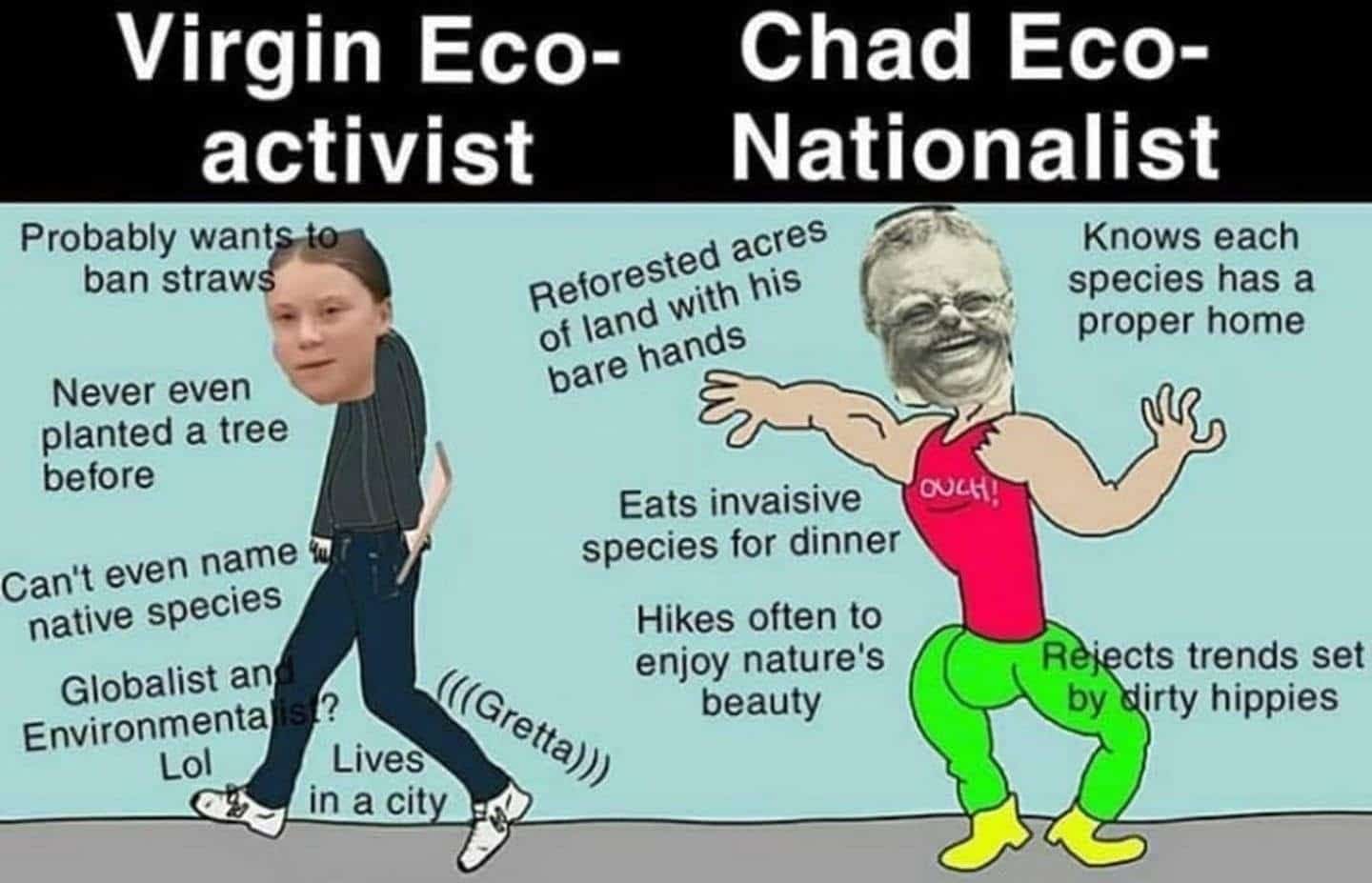

It is not only the outsider-species that are the perceived enemy of the Hungarian environment and the Far-Right Ecologists. An example of how ZE propagates a form of “Green Nationalism” (a coinage operationalized by Jobbik’s environmental section) is the critique of Danish pig farms, which polluted the ground waters in Csallóköz (initially picked up in a separate statement by HVIM). A fair amount of content posted on ZE deals with the misconceptions of ‘liberal environmentalists’, challenging their moral relativism mostly associated with hunting or veganism. An adequate representative of this ‘globalist’ and ‘liberal’ conception of environmentalism (in the words of Elek, “bleak and soulless” environmentalism that does not recognize the nations as organic elements) is Greta Thunberg, a high-school student from Sweden whose “climate strike” initiated the global climate movement, “Fridays for Future” in 2018.

Since Greta has been vilified by the global far right, it is no surprise that the ZE has followed the same trend. Portrayed as “The symbol of leftist idiocy”, Greta epitomizes the problematic sentimentality behind climate activism, and is juxtaposed to the expertise of those “who are really in the know”. Yet, such framings point to important ideological nuances. For instance, the belief in technocratic expertocracy is contradictory with the populist impetus behind most of the contemporary radical-right parties. This is a case in which conceptual demarcation from political scientists comes in handy: far-right movements such as HVIM are not fully ascribing to the Manichean populist demarcation between the ‘good’ people and the ‘corrupt’ elite. Instead, Elek and his like-minded fellows openly defended an antidemocratic, organic type of society, in which the country is perceived as a living organism, where the naturally gifted should be in charge of solving the environmental riddle. To back these arguments, ZE uses the ‘expert knowledge’ to prove the (minor) points not directly linked to the overarching claims associated with the antidemocratic organicism in the ecological domain. For instance, in support of hunting practices and meat-eating, ZE calls forth the ‘experts’: university professors from Szent István University in Gödöllő, domestic conservationists, but even internationally-known endorsers of the environmental cause, such as David Attenborough and Jane Goodall.

However, the problematic albeit shrewdly placed content of ZE is not always easy to recognize, as the Facebook page indeed posts (from the ‘liberal’ media such as Index, 444, and Qubit) some very useful tips on how to reduce our carbon footprints, both as individuals and as societies. From practical advice on how to reduce waste to more systemic, policy proposals on how to address e.g. deforestation, ZE has been actively engaging with the ‘practice of sustainability’, the more technical (and perhaps not as ideologically lucid) aspects of addressing the environmental change. The wide range of topics dealt with by ZE also cover climate change, breaking the (not entirely unwarranted) stereotype of far right being a flagbearer of climate skepticism. In fact, ZE is a stern critic of the indolence of Viktor Orbán’s regime in fighting climate change. Elek himself argued in our talk that ‘no real nationalist’ is a climate denialist, as that would presuppose ‘not caring about the future of your country’. Such positions have enabled the interaction with environmental politicians and activists (e.g. Erzsébet Schmuck from LMP), who have engaged with ZE’s posts.

Elek and Zöld Ellenállás serve as a reminder of an often-forgotten fact – that the beginnings of environmental concern were informed by conservative and even nationalist roots. The Facebook page often pays tribute to the founders of Hungarian conservationism (such as Otto Herman), or the international figures such as Ernst Haeckel, the founder of ecology as a scientific discipline, but also a follower of vitalist philosophy and a proto-fascist. By implying the synthesis of naturalism and nationalism, and the unity between the people, the nation, and the land, ZE’s implicit underwriting of the “blood and soil” invokes both a modality of eco-fascism and a broader ‘Far-right Ecologist’ (FRE) concern that emanates from such ideological strands.

The interactions visible on ZE posts also point to the fundamental issue of FRE’s impact on the ‘green transformation’: what kind of motives and intrinsic values does one bring on board when joining an ‘environmental’ cause? Does care for rivers, clean air or animals necessarily invoke cosmopolitanism? Environmental causes usually gather a wide (enough) range of supporters, of different political backgrounds and motivations. This might easily entail having far-right ecologists endorsing that new green area in your neighborhood, or working next to you on an organic farm. One of these ethical issues has affected the author of this text, who is partially responsible for the fact that ZE even exists, since Elek decided to set up the page inspired by our talk.

Being aware of these ‘grey zones’ is not to be apologetic towards the exclusionary and repulsive worldviews of their proponents, but to realize how the moral panic as a natural reaction to authoritarian ethnonationalism does not prevent its proponents from entering the sphere of debate. Much as it may be hard to admit it, every ingredient of environmental care: including the emotions and affections one may have towards the somewhat abstract and contested concepts such as “land”, “nature”, or “people”, can be positioned on the both ends (and the middle) of an ideological spectrum. It may seem difficult or even disturbing to embrace this finding, but the sooner we come to terms with this pluralism of alternatives (including Far-Right Ecologism and back-to-land antimodernist movements), the better we will be in framing environmental campaigns. Awareness of environmental issues depends on the mental maps we activate through metaphors. The burden of failure to do so is not that of ZE and the like-minded organizations, or the “people who just don’t understand”. After all, the struggle to preserve our planet and make it livable is much about communicating this crisis as it is about anything else.

Cover Photo: YouTube / Hatvannégy Vármegye Ifjúsági Mozgalom

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).