This dossier stems from the debate sparked by Elizabeth Suzanne Kassab’s article—which opens this collection—on the transformation of the Arab intellectual scene after 2011. Her notion of a “new contemporary” in Arab thought prompted a series of contributions that do not aim to offer solutions, but rather to raise new questions, probe unresolved issues, and put forward critical perspectives. Bringing together Kassab’s essay and two related pieces, the dossier explores how Arab thought is redefining itself in light of the uprisings, the failures of political transitions, and the moral and intellectual rupture marked by Gaza.

Dossiers

- The parliamentary elections on the 17th November saw victory for those in favour of secession from Serbia. It is likely that with effect from the 10th December Kosovo will unilaterally declare its independence. What will the consequences of this decision be for the region? The Kosovars see no other alternative. Serbia considers independence to be inadmissible, and has the support of Russia. The international community is divided. And so is Europe, which urges caution but risks proving itself once again to be impotent in the face of crisis in the Balkans. Yet now more than ever there would seem to be a need for an inequivocal stance.

- One year after her death, an exhibition dedicated to Oriana Fallaci has met with the usual success with audiences in New York, Milan and Rome. And once again it resulted in moved memories expressed by the media (most of all Rizzoli and Mediaset). Two sociologist, one French and the other Italian, once again ask themselves why Italians love Oriana Fallaci and her Lepenist school of thought so much. Are they racists? Her success in Italy and abroad reveals interesting information not only about those who love her last books, but also about our societies. This is the thesis embraced by Giancarlo Bosetti, Reset’s editor in chief, who has written a book about Fallaci, about “orianism” and thinking-in-terms-of-the-enemy.

- According to the Economist Pakistan is the most dangerous place in the world. And nevertheless, Pakistan boasts a long tradition of democracy. Its people is moderate and against terrorism. Its media are definitely freer than the average Arab country. Benazir Bhutto was the first Muslim woman to become Prime Minister. Its economy is growing by 7% on average per year. Pakistan could be a much more modern and attractive model for Islamic countries than the Saudi Wahhabi one. This is why on the next elections on 18th February, the future not only of Pakistan, but also a large part of the future of Islam is at stake.

- What does ‘democracy’ mean for you? Reset posed the question to two prominent intellectuals – one belonging to the Western tradition and one from the Arabic tradition. The result is the dialogue published below, which takes its starting point from a text written for Resetdoc by Carlo Galli. Andrew Arato, the editor of Constellations and professor of Political Theory at New York’s New School, does nothing to mask the limits of current Western liberal democracies, but states that democracy represents “the only response the the profound crisis of the Arab world.” The response of Hassan Hanafi, professor of philosophy at the University of Cairo, is caustic: "Democracy is a means, not an end, and liberal democracy is not the magic key that opens all the secrets of the world."

- What stance should the left adopt with regard to Islam and a multicultural society? Dialogue or cold war? In an article published in the magazine Reset, Nadia Urbinati of Columbia University initiated a long discussion with the Princeton philosopher Michael Walzer, editor of Dissent. Urbinati evoked post-war categories, internal criticism from Eastern dissidents, and the rejection of ‘block thinking’. Walzer adopted a more sceptical stance on dialogue, saying that criticism of extremists must come from within their own ranks. It is a crucial issue for today’s world, on which the philosopher Charles Taylor has also shared his views.

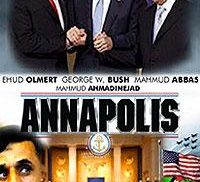

- Even symbols have a certain importance. This is why the Annapolis handshake between Abbas and Olmert can bring hope with the new talks between Israelis and Palestinians. But an agreement is still far away and two very serious conundrums are weighing down on the future of the region. Hamas, locked away in the prison that is Gaza, still does not want to recognize Israel. Meanwhile, Iran feels more and more surrounded, following the Syrian and Saudi participation in the conference. The Annapolis summit, which was lived out with more enthusiasm in Washington than in the Middle East, will be the umpteenth false start, a film which has already been seen? Or, despite the general skepticism, will represent the beginning of a new road to peace?

- Fear of the other is engulfing European cities. The xenophobic right of Christoph Blocher wins in Switzerland, trouble is brewing in the suburbs of Amsterdam, and in Italy hatred of Roma and Romanians is spreading. And yet the number of mixed marriages continues to rise in France, in the UK, in Italy and in the US, amongst others, uniting partners of different religion, different colour, different ethnic group and different nationality. They are the sign of a hope, of a society which opens itself up the ‘other’. They are couples formed often of people who are prepared to make compromises, and their children are destined to be even more open to the world. Beyond all prejudice.

- They marched for days, braving the wrath of the regime. The Burmese demonstrators caught the attention of the world with their demands for democracy, freedom and dignity. Their weapons were mobile phones, and their leaders Buddhist monks who have reminded the world how religion can sometimes contain a unique energy. Now, however, those sacrifices and those deaths, demand that the lights do not go out on Burma. More than two months after the start of the protests, what has become of the “saffron revolution”? Much lies in the hands of China and India, the two main allies of the military junta. But the West, too, can still play its part.

- Berlin, London, Cologne, Marseille, and now Bologna and Genoa. All over Europe the building of new Mosques is giving rise to disputes and protests. According to some in Italy there are too many Mosques; according to others there are too few. The media is blowing on the fire, and the fear of differences is mixing with Islamophobic provocations and more rational arguments. How transparent is the running of our Mosques? The left is divided. In Bologna, the mayor Sergio Cofferati says that Mosques guarantee more security than an improvised garage. In the face of protests, however, he is opting for a local referendum. In America, according to the Economist, everything is easier. And in Australia, a deliberative poll has showed that…

- The expected spectacular victory of the Moroccan Islamic Party of Justice and Development did not happen. But in the parliamentary elections of September 7th , the PJD proved itself to be an authoritative and responsible protagonist in a Morocco which is increasingly open and modern, despite the low turnout at the ballot box. Opening up the system to Islamic parties is a decision that cannot now be reversed for a country which wishes to call itself democratic. The people therefore have the freedom to choose, and the Islamic parties in turn are encouraged to open up, to engage in dialogue with secularists, and to come face to face with reality. Just as has happened in Turkey with Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP. But can Ankara serve as a model for Rabat? After Turkey, might Morocco also have the right to a claim for EU membership?